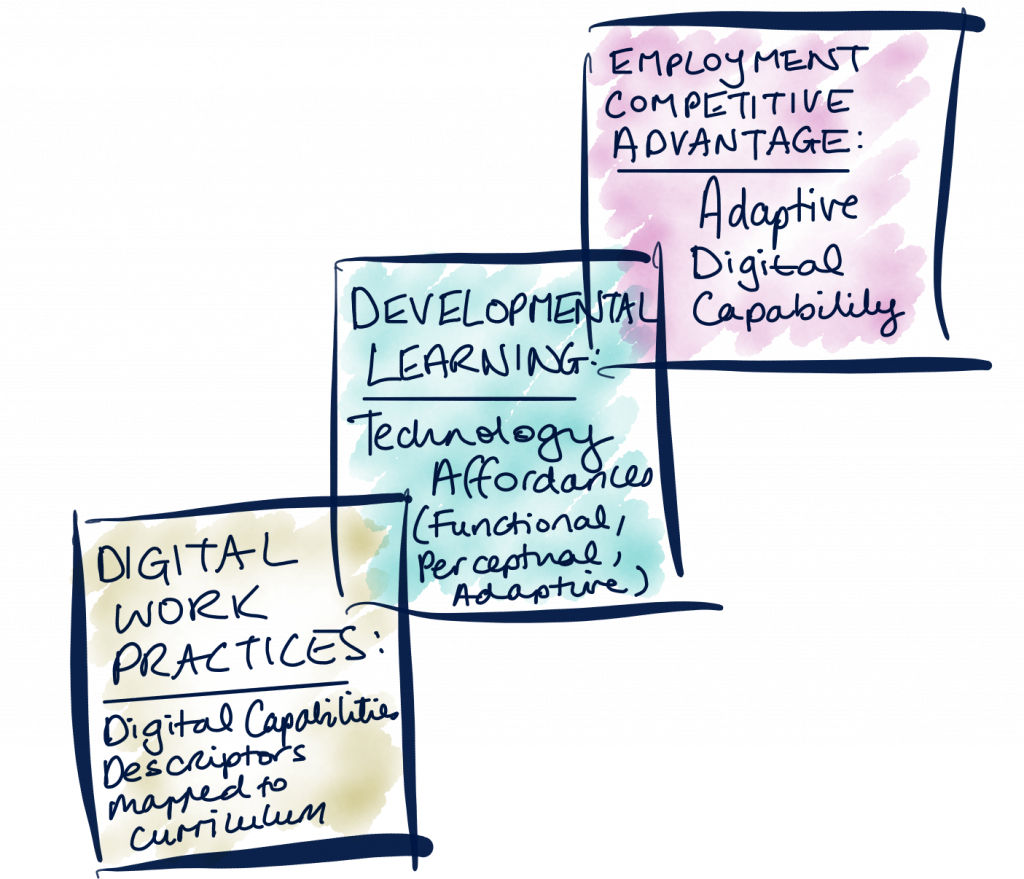

Digital Affordance Developmental Learning Model

Graduates who have developed Adaptive digital capability, in particular, potentially have a competitive advantage for graduate employment. Adaptive digital capability is in high demand and short supply, according to the analysis undertaken in this project.

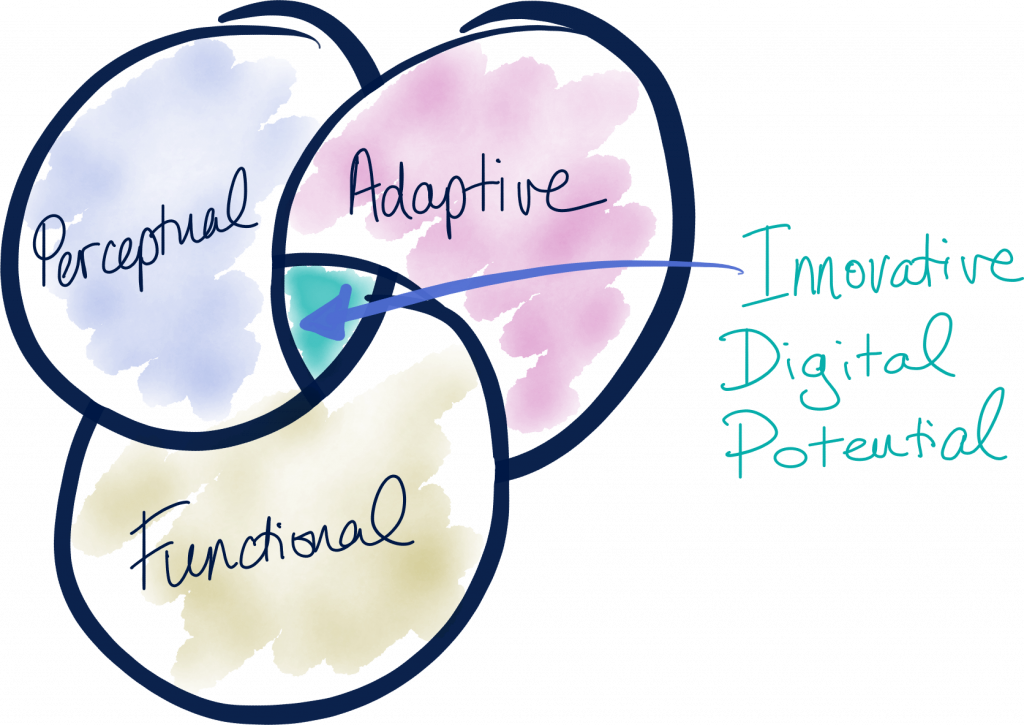

Figure 1: Digital Affordance Developmental Learning Model

Affordance theory defines a technology in terms of the uses, interactions and possibilities that the technology affords to its users (Best 2009; Evans et al. 2017).

The developmental learning ideas integrated with affordance theory are informed by educational theory, including hierarchies and stages of learning with acknowledgement of the learner, the environment, the outcomes and increasing complexity; and highlighting the importance of reflection-in-action for professional learning and practice in unpredictable, unexpected and new circumstances (e.g., Piaget 1936; Bloom 1956; Biggs and Collis 1982; Schön 1983; Gagné 1984; Anderson et al. 2001; Scott 2016; Stein 2017).

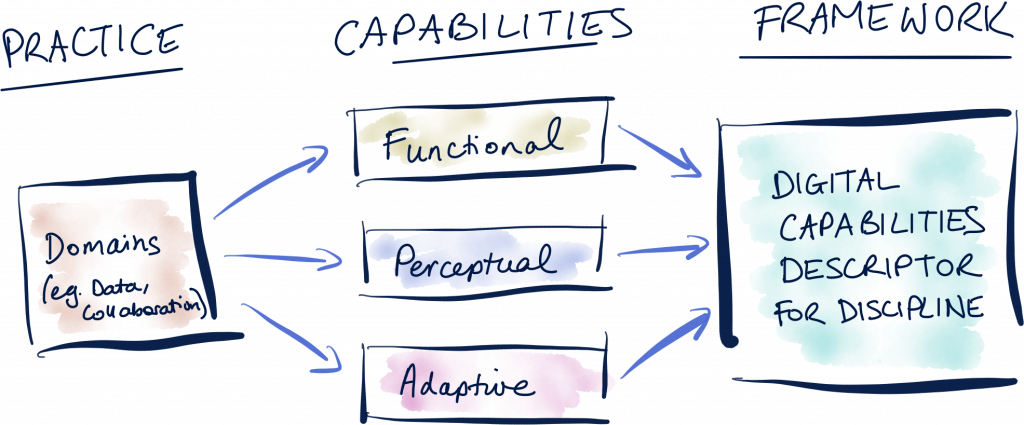

Figure 2: Digital affordance concept

For the purposes of this project, digital affordances are defined as follows:

- Functional affordances relate to the operation of technology; this includes naming, knowing and operating the features of a technology/technologies to perform tasks.

- Perceptual affordances relate to interpretation and being discerning about technology tools and practices for their suitability and in-context operation for outcomes in known contexts.

- Adaptive affordances relate to imagining, adapting and extending technology use in previously unexplored and emerging contexts for innovative outcomes; this requires some functional knowledge/skills and perceptual experience.

(Source: adapted from Best 2009; Evans et al. 2017; Fray et al. 2017)

Over time, the learner ideally develops digital capabilities across these three hierarchical but integrated layers.

Adaptive capability requires some Functional knowledge/skills and Perceptual experience; this may involve knowing enough to work with specialists, rather than having well developed Functional skills oneself.

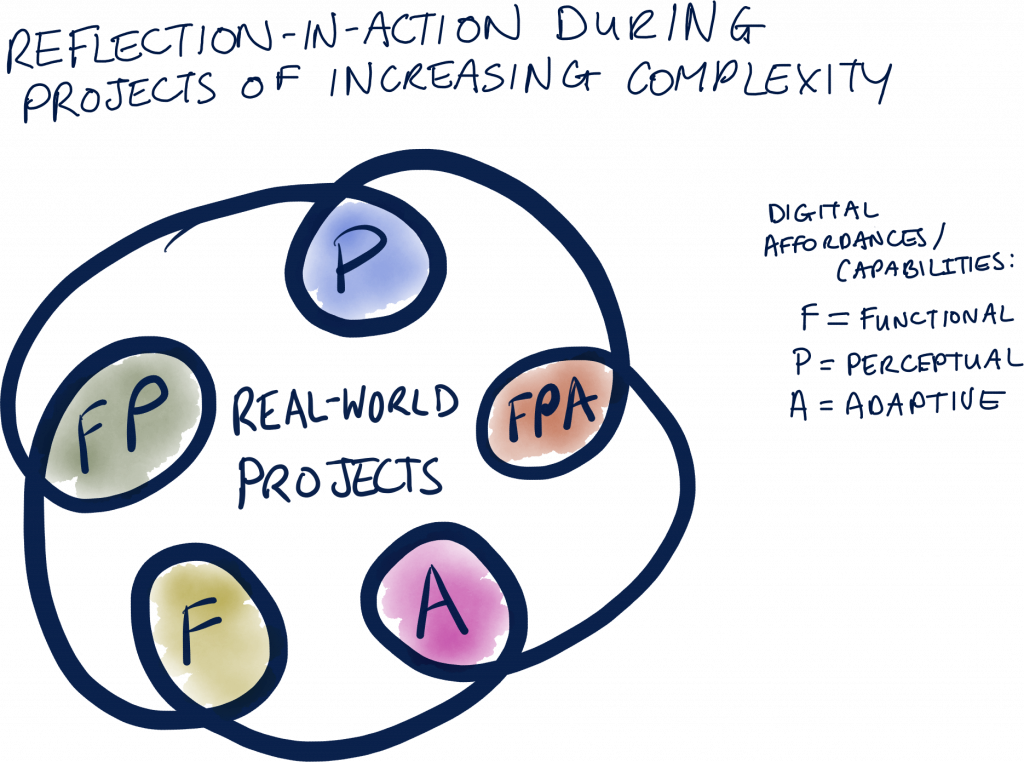

Reflection-in-action (Schön 1983) is integral to this learning process.

Figure 3: Reflection-in-action for building adaptive capability

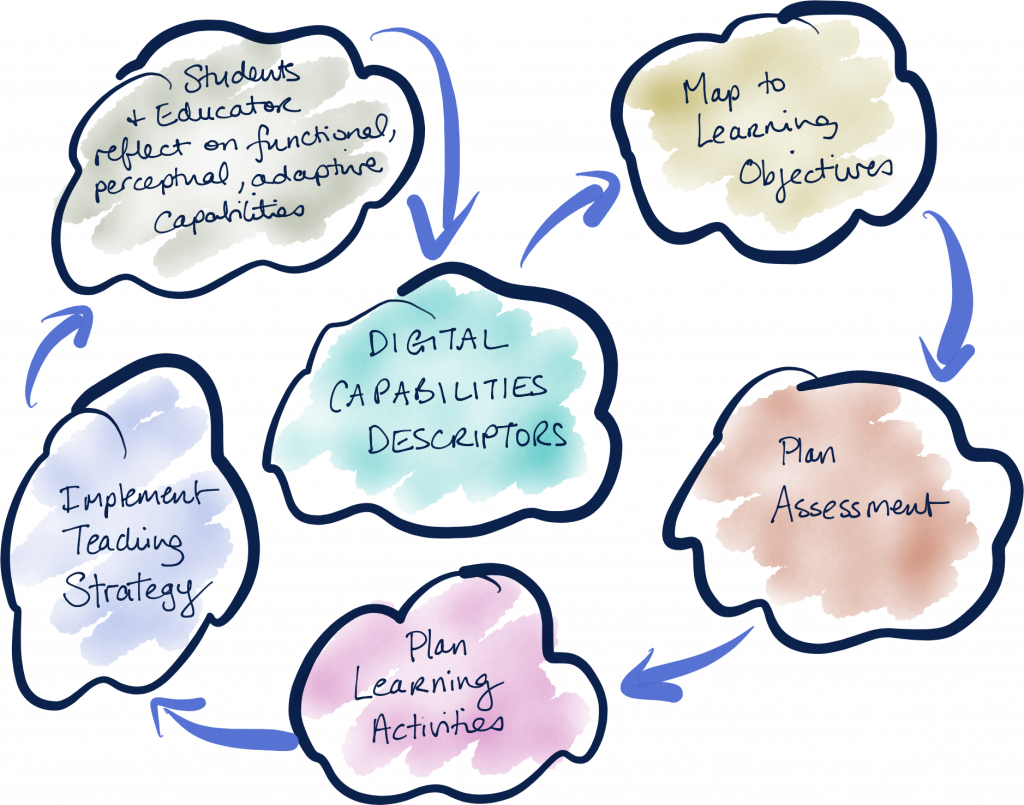

Action research cycles have underpinned the iterative development of the learning model as a rapid prototype, with discipline-specific Digital Capabilities Descriptors at its heart. Cycles of industry, educator and student input have been integral to the rapid prototype process.

The Descriptors interpret affordances in sample domains, which are categories of practice and related capabilities for existing and emerging jobs/roles.

The Descriptors start with identifying sample domains of digital practice e.g. data.

The domains might involve digital capabilities that are general and applicable across disciplines (e.g. collaboration) or specialised for specific disciplines (Beetham 2015). What is a general capability in one discipline might be a specialised capability in another.

The domains of practice were then interpreted and described in terms of Functional, Perceptual and Adaptive capabilities.

Figure 4: Framework linking digital practice to capabilities through affordance lenses

Being truly ‘Adaptive’ at the most advanced level would involve pushing boundaries with the use of technology in new ways in new contexts (i.e. not only new to the learner).

Realistically, we can support students in working towards this aspiration, with emphasis on imagination and ‘seeing’ possibilities, rather than expect that all graduates will be capable of true innovation with technology. Similarly, in the ‘Functional’ and ‘Perceptual’ layers, there may be a spectrum of lower to higher levels of capability.

Expectations also need to relate to the Australian Qualifications Framework (AQF), so we would not have the same requirements for Bachelor degree and Master degree students. However, using the three lenses of Functional, Perceptual and Adaptive can help to frame and express learning about the use of technology in contemporary and future work practices.

Although the Functional, Perceptual, Adaptive scaffold can be implemented in a linear way, it is highly recommended instead that the affordances are considered holistically and the layers are integrated.

Educators could emphasise particular affordances in different ways at different times, depending on their students’ stage of learning, the context, the learning outcomes, etc. It is also highly recommended that Adaptive capability development is emphasised most strongly as the student approaches graduation.

The Digital Capabilities Descriptors developed for Journalism, Design, Engineering, and Music Industry are intended to illustrate ways in which affordance theory can be interpreted for scaffolded or developmental learning about industry-relevant digital work practices in different disciplines.

Digital Capabilities Descriptors can be used in different ways, such as:

- guiding the design of assessment and learning activities to enhance existing curriculum

- guiding new program and course/unit development

- guiding teaching plans focused on particular technology

Figure 5: Digital affordance developmental learning model in action

Implementation of the model involved pilots with sample groups of students. The teachers involved highlighted the importance of three success factors:

- whole-of-program approaches to implementing the learning model as opposed to isolated interventions

- support for students to adopt reflective, analytical and evaluative approaches to the uses of technology

- students able to position and discuss their work as demonstrating Functional, Perceptual and (ideally) Adaptive digital capabilities, with insights into further growth needed.

References

Anderson, L., Krathwohl, D., & Bloom, B. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. New York: Longman.

Beetham, H. (2015). Deepening digital know-how: Building digital talent. Key issues in framing the digital capabilities of staff in UK HE and FE. Report, JISC, UK.

Best, K. (2009). Invalid command: Affordances, ICTs and user control. Information, Communication & Society, 12(7), 1015-1040.

Biggs, J., & Collis, K. (1982). Evaluating the quality of learning: The SOLO Taxonomy. New York: Academic Press.

Bloom, B. (1956). Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The classification of educational goals, Handbook 1: Cognitive domain. New York: Longmans Green.

Evans, S. K., Pearce, K. E., Vitak, J., & Treem, J. W. (2017). Explicating affordances: A conceptual framework for understanding affordances in communication research. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 22, 35–52.

Fray, P., Pond, P., & Peterson, J. F. (2017). Digital work practices: Matching learning strategies to future employment. In Proceedings of the Australian & New Zealand Communication Association (ANZCA) Conference, University of Sydney, Australia, 4-7 July.

Gagné, R. (1984). Learning outcomes and their effects: Useful categories of human performance. American Psychologist, 39(4), 377-385.

Piaget, J. (1936). Origins of intelligence in the child. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Schön, D. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. London: Temple Smith.

Scott, G. (2016). Transforming graduate capabilities & achievement standards for a sustainable future. Final Report. National Senior Teaching Fellowship, Sydney: Australian Government Office for Learning and Teaching, May.

Stein, V. (2017). Stanford professors will use a $1 million grant to change the way undergraduate scientists learn. Stanford News, 13 December. Retrieved from news.stanford.edu