Essay by Drey Willows as part of Contextualising Practice course.

Content Warning: This essay discusses loss, grief and trauma.

On the 16th of April, I spoke to you in text. We spoke about how it would be great to catch up when the restrictions eased and how weird it was that your new job included telling people they couldn’t sit on the beach. So many times, I have wished I had said more to you on this day. What would I have said to you if I had known it would be the last time I would ever speak to you? I have re-read your texts; I hear them in your voice.

In April 2020, my cousin suddenly died in a high-profile traffic incident on the Eastern Freeway, Victoria. Glen, along with three other police officers, were killed when a truck collided with them on the side of the road. The shock and devastation was amplified by the traumatic nature of the event and the intense public and media interest in the case. Bereavement rituals were largely denied to my family due to the strict COVID-19 restrictions in place at the time. This paper discusses how my lived experience of this tragic event has manifested in my creative practice and how this process has facilitated a greater understanding of my grief and trauma. As I have a professional background as a crisis response social worker, I have clinical knowledge and education in these areas that underpins and informs my worldview. As such, I will use a psychoanalytical lens, specifically contemporary grief and trauma literature, to discuss two artworks I created in response to my personal experience from 2020 – 2021. As a printmaker, I will be discussing how print techniques, processes, and materials have been fundamental to expressing the conceptual meaning of my work. The works I will be discussing were created at two pivotal moments in my journey. The first, Looking Up (2020), was created in the immediate aftermath of Glen’s death, at a time when the shock and devastation were felt most strongly in my physical body. I will examine how I used print techniques, pressure and interference, to reach for meaning during a highly disruptive period of my life. The second work I will be discussing, Inner Bloom IV (2021), was created a year after Glen’s death. This work speaks to the transformative nature of grief and trauma. I will explore how I used symbolism and print techniques, strain and transference, to redefine and continue my bond with Glen, and to acknowledge the painful post-traumatic growth I have experienced. Psychologist Danielle Knafo (2012) explains that many artists draw creative energy from their lived experiences of trauma and death and by doing so, provide themselves and their audiences the opportunity for an authentic relationship with loss, death, and the horrors associated with life. It is not my intention to demonstrate the effectiveness of art as therapy, rather I am providing a narrative for my lived experience that speaks to the ubiquitous nature of loss and death, and profound encounters with grief and trauma.

On the 22nd of April, my world completely shattered. How many times had I been there with people on the worst day of their lives? Bearing witness to, not turning away from their distress. I always thought I understood better than most that everything can change in an instant, and maybe I do, but nothing can prepare you for when it happens to your family.

Grief researchers Milman et al. (2017) refer to those grieving a loss due to homicide, suicide, or a fatal accident as violent bereavement. Disproportionate levels of distress and the possibility for prolonged grief symptomology are significantly higher than people grieving a non-violent death. This is attributed to violent bereavement hindering meaning-making in the aftermath of the death (Milman et al. 2017). In a systematic review of the literature regarding the use of visual art with the bereaved, meaning-making during bereavement was defined as the ‘ability to develop new goals and purpose, or to construct a sense of self that incorporates the significance of an experience’ (Thompson and Janigian 1988, cited in Weiskittle and Gramling 2018:11-12). In the aftermath of Glen’s death, I created a mixed media work, Looking Up (2020; figure 1), which included monoprint, collagraph, and collage on paper. This work was created at a time when my life had been completely ruptured. Largely process-driven, the work was an intuitive expression of raw internal and external turmoil. The work shows a collaged silhouette of an indigo and white female figure, the negative space inside her body are botanical impressions taken from the flowers I had been given after Glen died. The positive impressions from the flowers frame the figure, as they curl around her from above and below. The collagraph eye is the focal point as she looks to the heavens in earnest. Psychotherapist and artist Maya Gronner Shamai explains ‘art allowed me to feel my pain, to document, touch, expose, suffer, and – mostly – to engrave a meaningful memory’ (Metzl and Gronner Shamai 2021:3). Echoing these sentiments, I expressed my shock and grief through a print-informed creative process where words failed me.

Pressure is a fundamental part of many print processes. In the case of monoprint and collagraph, the matrix is covered in ink and then transferred to the support, under the force of pressure to make that transfer possible. The matrix is the object that bears the image to be transferred and the support is the surface that receives the image. Art scholar Jennifer Roberts (2021b), discusses the unique tension in printmaking between pressure and delicacy, explaining that prints born under pressure are a record of this tension and this provides an intimate insight. For Looking Up, this process was particularly laborious as I did not have access to a printing press throughout lockdown, so all printing was completed by hand. Metaphorically, this speaks to art theorist Jill Bennett’s (2005) description of how the force of trauma imprints upon the body, becomes part of the body, rather than something one processes and works through. This is an essential component of this work as in the months following Glen’s death, my immediate reaction was felt most strongly within my body due to the shock overwhelming my mental capacity to comprehend the magnitude of what had happened. Psychiatrist Thomas Fuchs (2018) explains in their writing on the phenomenology of grief, that the initial response to a sudden death often resembles a physical reaction in the body, of being paralysed in shock and despair. The distinction between physical and mental pain is blurred as symptoms include a feeling of heaviness, restrictiveness, and pressure, especially around the heart, chest, and throat. The process of creating Looking Up required patience, physical exertion, and restraint. The application of pressure became the record of the relationship between my body and my emotional state.

Feminist scholar Gwen Raaberg (1998) discusses how the act of creating a collage piece together fragments, using found and recycled materials to create new configurations that subvert and speak to the private and public spheres. Looking Up utilises collage to combine abstracted botanical monoprints to create the female silhouette. The process of collage was important in forming the narrative of this work, the physical act of tearing and cutting the fragments to be reframed spoke to the distorted sense of reality that engulfed me. Fuchs (2018) discusses temporality in grief, explaining the bereaved sit in the separation of time between the present and the past in their connection with the deceased. This speaks strongly to my experience as my worldview was deeply shaken when Glen died. I had subconsciously assumed that there would be ample time for our relationship to continue. However, after he died, I was forced to reckon with the reality that this future no longer existed and, as time progressed further from the date of his death, I felt distressed at the prospect of this threatening my connection to him. Interference in printmaking is a method that stretches materiality, bringing together resources that may be otherwise inconsistent to create new meaning. Through literal interference, triggered by materials colliding with one another, a sudden and unpredictable new meaning occurs (Roberts 2021a). Through collage, I cut and tore through materials, I glued the fragments back together in organic formations, as I grappled to redefine my identity and make sense of a nonsensical time.

When I think back to the day of your funeral, it feels like I am having an out-of-body experience. It’s hard to believe this could feel more surreal, but there I sat in my blue dress, watching your service through my laptop. The celebrant said something that swirled around my head, as I watched the ten people permitted to be in the ‘covid-safe’ chapel. ‘If only you could see how many eyes are watching right now,’ he said, ‘the room is actually overflowing.’

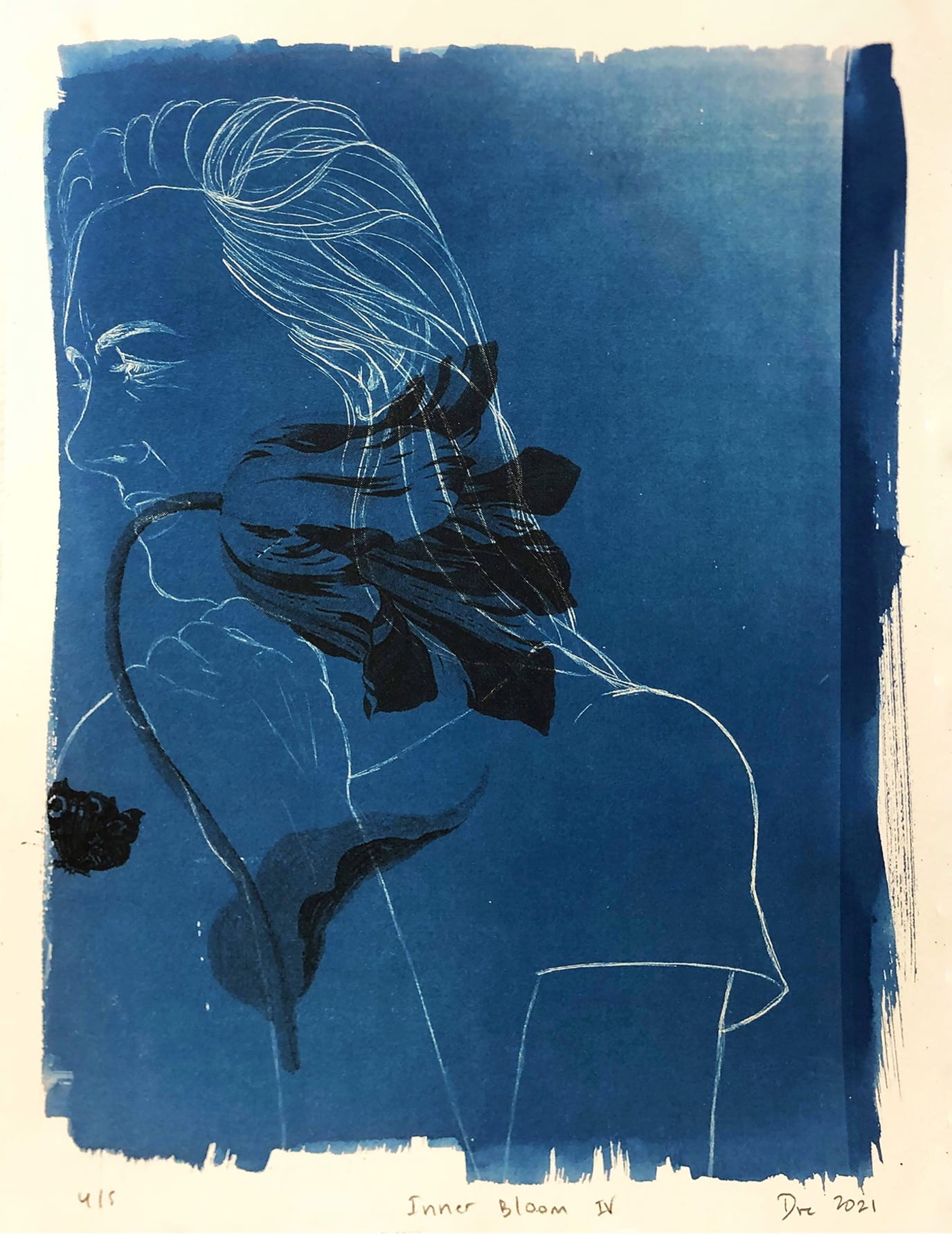

Art academic Barbara Bolt (2007) challenges predominant thought regarding materiality in art as being a means to an end, instead suggesting the relationship between artist and materials is a reciprocal and collaborative process. Bolt uses the work of philosopher Martin Heidegger (1977), who uses the term ‘concernful dealings’ (cited in Bolt 2007:1) to describe the conversation that occurs between an artist and their materials in creating art. This strain of thought is significant to the work Inner Bloom IV (2021; figure 2), created a year after Glen’s death. The work was created using cyanotype and screen-printing techniques and shows a white line drawing of a female figure on a Prussian blue background. The brush marks are evident around the edges of the blue border. The figure is to the left side of the frame, appearing to turn away from a subtle light that emulates from the top right corner. Her expression appears distressed as she casts her gaze downwards. Layered on top of the figure is a halftone black flower that curves around the contours of her hand and through her mouth. Floating over the figure’s chest is a halftone black butterfly. At the time I created this work, I was beginning to understand my life had irrevocably changed. To express these changes, I collaborated with the materials to facilitate a greater understanding of my experience.

The techniques used to create Inner Bloom IV, cyanotype and screen-print, use stencilling matrixes to expose the image using ultra-violet light to an emulsified surface. Transference is fundamental to printmaking as all prints are created via this relationship between transferring an image from matrix to surface (Roberts 2021b). Roberts (2021c) explains the halftone used in screen-print, where the photographic image is broken down into small dots, creates a pattern from the image that can be recognised by the silkscreen as the ink is strained through to the surface below. The flower and butterfly motifs in Inner Bloom IV have symbolic meaning, the flower to growth and the butterfly to metamorphosis. However, from a materiality perspective, the use of screen-print and halftone are strongly linked with the strain of the painful and awkward personal growth I was experiencing at the time this work was made. The flower and butterfly images emerged in this work via a process of transference. First, the halftone stencils were exposed onto the screen via light and then pushed through the screen using ink. The halftone dots are tiny and from a distance are not discernible as separate from one another. This relates to philosopher Kym Maclaren’s writing regarding intense and profound grief. Maclaren explains the bereaved are ‘faced with a crumbling of [their] world; it can no longer exist with the meanings that it had (2011:60). Maclaren (2011) identifies that for the bereaved to continue living, they engage in a process of metamorphosis and live in a transformed world. By physically breaking down the images of the flower and butterfly into a halftone and harnessing light and matter to expose and print the images onto the surface, I transformed the images to an altered version of themselves. Like the halftone dots, these alternative versions may not be immediately obvious to the viewer, nevertheless, the change is there.

‘I have woven

a parachute out of everything broken.’

-William Stafford (cited in Sullivan et al. 2005:102)

Recent research in grief studies conducted by Black et al. (2022) supports the argument that redefining one’s connection with the deceased is adaptive rather than inhibitive in bereavement recovery. Continuing bonds is the widely used term that encapsulates one’s ongoing relationship and attachment with the deceased (Black et al. 2022; Fuchs 2018; Milman et al. 2017; Weiskittle and Gramling 2018). Black et al. (2022) made the important distinction between internalised and externalised continuing bonds. Internalised continuing bonds refers to reflective contemplation and deliberate rumination, as opposed to externalised continuing bonds that speak to one’s inability to recognise the finality of the death, experiencing intrusive thoughts and images of the deceased. For this paper, I will be referring to internalised continuing bonds. As mentioned earlier, a source of personal distress was the fear that as time continued, my connection with Glen would dissipate. By intentionally engaging with my lived experience of grief and trauma, I leaned into a continuing bond with Glen. Art psychotherapists Einat Metzl and Maya Gronner Shamai (2021) concluded that through creative representation of one’s grief, the bereaved may express deep emotions, reflect on internal processes, and redefine their relationship with the deceased. Black et al. (2022) found that continuing bonds with the deceased were related to greater grief intensity, however, this was not identified as maladaptive in grief recovery where the bereaved experienced post-traumatic growth. Post-traumatic growth is described as the emergence of positive changes that occur following a traumatic event, that exceed growth that might otherwise occur (Black et al. 2022). My lived experience is consistent with research by Black et al. (2022), who identified that actions associated with continuing bonds, such as intentional rumination and reflective contemplation about the deceased, were associated with greater post-traumatic growth. Through creative engagement with my pain, I came to know myself as a resilient, open person, with greater appreciation for the fragility of life, as well as a deepened understanding of the horrors of life and death. My post-traumatic growth is difficult to articulate, yet I know that I am profoundly changed. By creating physical work about Glen’s death, I committed his tangible enduring presence into my life, and this strengthens my continuing bond with him. It should be noted that, as the experience of grief and trauma are non-linear, so too is my sense of enduring connection to Glen. It is at times unstable and an ever-open wound.

‘What is stronger

than the human heart

which shatters over and over

and still lives’.

-Rupi Kaur (2017:107)

This paper has focused on two artworks created at pivotal moments throughout my lived experience of profound grief and trauma. By using contemporary grief and trauma literature, coupled with an exploration of print-specific techniques and materials, I have discussed how the loss of my beloved cousin has manifested in my creative practice immediately after his death, and after the first anniversary. Terminology that may be used interchangeably when referring to bereavement and print, such as pressure, interference, strain, and transference, has given me the language to describe the concernful dealings I undertook in collaboration with my materials to encapsulate my experience and better understand my changed reality after Glen’s death. Although the creation of these works has not reduced the intensity or duration of my symptomology, the process and subsequent reflection has cultivated a pathway to meaning-making, fostered a continuing bond with Glen, and has provided an acknowledgment of the post-traumatic growth I have experienced.

REFERENCES

Bennett J (2005) Empathic Vision, Stanford University Press, California.

Black J, Belicki K, Emberley-Ralph J and McCann A (2022) ‘Internalized Versus Externalized Continuing Bonds: Relations to Grief, Trauma, Attachment, Openness to Experience, and Posttraumatic Growth,’ Death Studies, 46 (2): 399-414.

Bolt B (2007) ‘Material Thinking and the Agency of Matter,’ Studies in Material Thinking, 1 (1): 1-4.

Fuchs T (2018) ‘Presence in Absence. The Ambiguous Phenomenology of Grief,’ Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 17 (1): 43-63.

Kaur R (2017) The Sun and Her Flowers, Simon and Schuster, Toronto.

Knafo D (2012) ‘Creative Transformations of Trauma: Private Pain in the Public Domain and the Clinical Setting,’ Dancing with the Unconscious: The Art of Psychoanalysis and the Psychoanalysis of Art, Taylor and Francis Group, New York.

Maclaren K (2011) ‘Emotional Clichés and Authentic Passions: A Phenomenological Revision of a Cognitive Theory of Emotion,’ Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 10 (1): 45-65.

Metzl E and Gronner Shamai M (2021) ‘I Carry Your Heart: A Dialogue About Coping, Art, and Therapy After a Profound Loss,’ The Arts in Psychotherapy, 74: 1-8.

Milman E, Neimeyer RA, Fitzpatrick M, MacKinnon CJ, Muis KR and Cohen R (2017) ‘Prolonged Grief Symptomatology Following Violent Loss: The Mediating Role of Meaning,’ European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8: 1-13.

Raaberg G (1998) ‘Beyond Fragmentation: Collage as a Feminist Strategy in the Arts,’ Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature, 31 (3): 153-171.

Roberts JL (2021a) ‘Interference. Contact: Art and the Pull of Print’ [streaming video], National Gallery of Art, accessed 31 May 2022. https://www.nga.gov/research/casva/meetings/mellon-lectures-in-the-fine-arts/roberts-2021.html

Roberts JL (2021b) ‘Pressure. Contact: Art and the Pull of Print’ [streaming video], National Gallery of Art, accessed 31 May 2022. https://www.nga.gov/research/casva/meetings/mellon-lectures-in-the-fine-arts/roberts-2021.html

Roberts JL (2021c) ‘Strain. Contact: Art and the Pull of Print’ [streaming video], National Gallery of Art, accessed 31 May 2022. https://www.nga.gov/research/casva/meetings/mellon-lectures-in-the-fine-arts/roberts-2021.html

Sullivan EJ, Rico G, Brown M and McCollum-Clark K (2005) ‘Reviews,’ The Journal of the Assembly for Expanded Perspectives on Learning, 11: 97-107.

Weiskittle RE and Gramling SE (2018) ‘The Therapeutic Effectiveness of Using Visual Art Modalities with the Bereaved: A Systemic Review,’ Psychology Research and Behaviour Management, 11: 9-24.