Essay by Yvonne Rambeau for Contextualising Practice

Introduction

The process of art-making can vary greatly from artist to artist. Though many feel the need to exert control over uncertainty through an ordered and planned process, American art educator Erica Richard advances that embracing improvisation and spontaneity can often enrich one’s creative practice (2000). I have learned myself that working in a fixed and linear way leads, more often than not, to a state of dissatisfaction with my artistic practice.

A few months ago, I was interested in making a sculpture exploring skin and bone, and had conjured up a mental image of an abstracted steel rib cage covered in a sheet of latex, pulled taut over the metal bones. With the deadline of an assessment looming, I quickly set myself to work. Diligently, I drew a preliminary sketch of the work and measured the dimensions required. The following week was spent laboriously cutting steel rods, curving them, grinding their ends to a point and welding them together – lo and behold the ribs! In the meantime, the sheet of latex had come to fruition over the course of many sessions spent in the fire escape, brushing the pungent liquid onto the wall in thick, yellowing layers. Following this undeviating path from the desk to the workshop, and from the workshop to the installation room, the sculpture was finished. Though perfectly on time, it felt dull and lifeless. I felt deeply unsatisfied looking at it: the piece was technically successful, but it lacked a certain essence. Images of my previous sculptures – dear to me – whirled in my mind. How did they elicit such a feeling of affection and kinship that this work hanging before me did not? It dawned on me that my artworks that had felt the most alive had been infused with what American artist Sarah Sze describes as an energy that only a process of experimentation, intuition and improvisation could create (2012). Though seemingly unorganised, this approach to art-making has consistently been the most fruitful to me. As French-born American author Anaïs Nin observes in her journals on the act of writing: ‘[i]t is almost impossible to detect the links by which one arrives at a certain statement. There is a fumbling, a shadowy area. One does not arrive suddenly at the clear-cut phrases I put down. There were hesitancies, innuendos, detours.’ (1973:84). This essay attempts to elucidate and celebrate this ‘fumbling’ that occurs within my artistic practice.

It is important to note that the following components have intentionally not been numbered as my art-making is not a linear, step-by-step process. The elements listed below are to be seen not as instructions but as a compilation of the actions that I may undertake as I create an artwork. I will outline my intuitive and improvisational process using a few of my works to illustrate my approach to art-making. This essay will be framed through the theoretical lenses of vital materialism and affect theory, alongside further writings on creative process.

An encounter with an object

Many ideas and feelings can arise from coming across objects. Through these unexpected encounters, found objects have often been a starting point for my artworks. Whether from walking down the street, or looking out of a window, these objects have diffused their energy to me. At times this can be an idea of a composition, or a captivating form, at times an essence that is indescribable yet undoubtedly tangible. American political theorist and philosopher Jane Bennett investigates this relationship between human subject and non-human object in her 2009 book Vibrant Matter. In it, Bennett challenges the traditional western perspective which views matter as passive and inanimate by positing the theory of ‘vital materialism’ (2009). According to this notion, non-human objects possess an active agency of their own, a force that affects other entities and systems – ‘thing-power’. One such instance in which I was affected by thing-power occurred when I was walking down the street one day with a friend. We passed a pole that had been wrapped in chains and ropes, and I couldn’t help but walk back and take a photograph of it (see Figure 1). I felt an inexplicable pull towards this thing which stopped me in my tracks. This later served as inspiration for multiple artworks of mine, which investigated the material qualities of metal chains, as well as the feelings and themes that they evoked.

I believe that there must also be a certain openness within the artist to be touched by the energy of things – an observing of the world around you and a sensitivity to be affected by it. Jonas Frykman and Maja Povrzanovic Frykman describe this as an ‘affective attunement to the world’ (2016:11). Although the term ‘affect’ is frequently used synonymously to emotions or feelings, author Eric Shouse defines it instead as an intensity which precedes consciousness and is experienced in a visceral, bodily manner (2005). In this sense, being attuned to the affects in the world entails an openness to the intensities that may be experienced when encountering something. It is one thing to come across an object, and it is another thing to feel its vitality and to be receptive to the affect that it may arise within you.

A feeling

These unexpected encounters with things and their thing-power can elicit the feeling of something significant being transpired, which I have often found to be difficult to identify in that moment. Although undefinable, it is nonetheless clear that something important has taken place, that a potentiality has transpired. British artist and psychoanalytic psychotherapist Patricia Townsend describes this feeling as a ‘hunch’ – a tangible sense that arises when something from the outer world chimes with the inner world of the artist (2019:8). Townsend advances that this feeling, though often inexplicable in the moment in which it occurs, can allow for an inkling of an idea to begin to form within the artist. Referencing psychoanalyst Christopher Bollas, Townsend explains that this process can be either intentional or accidental (2019). At times, the artist may actively search for and succeed in finding a source of inspiration; at times, they may unexpectedly discover something that begins to nourish their imagination.

A set of materials

I often start a sculpture with a material, or a set of materials that appeal to me for various reasons. Beginning with materials can be a wonderful way to generate ideas by listening intuitively to what they say to you. This material-based approach is adopted by American artist Robert Barry, for whom ‘ideas come out of objects’ (2009). This can manifest itself in my practice through the use of found objects, which may spark my interest through an intriguing form, a particular material quality that it may possess, or an emotion that it may evoke within me. Alternatively, I may intentionally seek out certain materials to use in particular processes or to represent a theme. A more concrete example of this is my penchant for found, used metal objects and the ability for their intensity to be felt in a bodily way. For example, steel chains elicit, for me, the heaviness of a body that has been hurt.

A series of tests, experiments

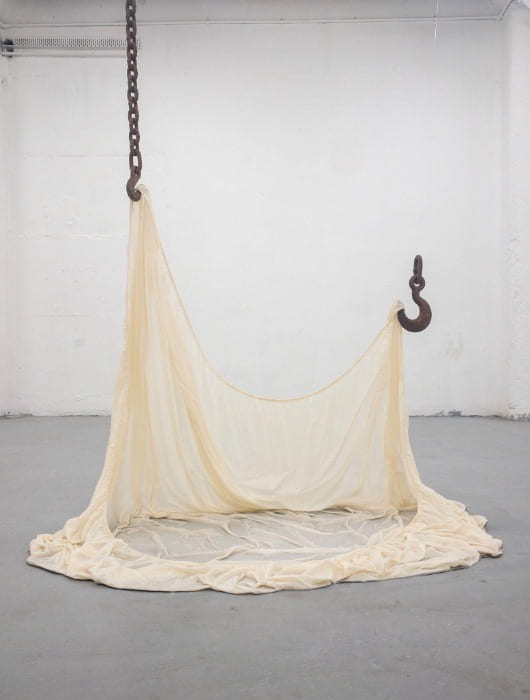

Arguably one of the most significant parts of the artistic process is the making. This does not necessarily mean the making of a work, but the act of making itself – experimenting with various materials and the possibilities that they offer, on their own or between one another. With this approach, my focus is on the act of making and not on a fixed and determined result. German artist Joseph Beuys refers to this openness to being led by the process of making: ‘I am prepared to do a thing without knowing where it goes’ (1980). I have found that creating in this state of improvisation and spontaneity allows ideas to flourish organically through the act of making. When working on my sculpture I’ll Make My Own Bed (see Figure 2), I was feeling unwell, but had set upon myself to explore the possibilities that my materials – a set of rusted metal hooks and chains, and an old bed sheet – offered to me. I suspended the chains, tested different heights, different directions to pull them in. I let them coil on the ground in a heavy and condensed heap. I placed the corners of the sheets on the rusted hooks and alternated their positions, allowing the sheets to hang in the air or drape on the floor. I worked the entire afternoon in spite of my sickness, and eventually realised that what I needed was to lie down. My gaze met the sheets at my feet and I noticed that I had created, in my fatigued state, a nook that perfectly fit my body in the foetal position. I curled in and closed my eyes, finding a feeling of comfort in and contentment with the piece.

Working with the materials in this process is significant. Edward Sampson calls this an ‘acting ensemble’ (quoted in Bolt 2007:3) – a notion encompassing the emerging relationships between the human actor, the material actors and other external factors that may be present. In my situation, the acting ensemble was composed of the found metal chains and hooks, the bedsheet, the installation space, my fatigue, and my body – all of us coming together to form the work. The focus is thus shifted away from the individual artist in favour of an active dialogue between all the actors involved in the making process.

A click

After working on a piece for some time – a chronology which could range from minutes to months – there can arrive a moment where it simply feels complete. I have not felt this way for all of my artworks: my interest at times wanes, or I may not feel the desire that pushes me to carry a piece through. But on wondrous occasions, my efforts feel like enough, and I am able to step away with a feeling of finality. I have found these moments to not be grand, but rather simple and humble in nature. American artist Bruce Nauman describes this as an instant when ‘it all kind of works, and you say, ah.’ (2001).

When working on my sculpture White Flag (Soft Axe) (see Figure 3), I had been playing at length with different compositions and I resolved to finalise the work. Looking at the chain hanging from the ceiling, onto which I had hooked a solidified singlet, I felt unsatisfied as the work seemed resolutely unfinished. On a whim, I decided to flip everything upside down. The singlet now hung from a hook that I attached to the ceiling, and was weighed down by the chain which was now hanging from a singlet strap all the way to the ground. The work truly transformed before my eyes, and I knew that that was it.

(At times) A realisation, retrospectively

An instant of new understanding can sometimes occur once the artwork has been completed. Indeed, similarly to American artist Judy Pfaff (2012), I can become so absorbed in the making of a work that I might only understand what it expresses, or uncover an entirely new dimension to it, once the process has ended. I have realised before, either by my own connecting of the dots or by another person’s comment, that my works have been much more than intuitive experiments. Rather, they have often been subconscious expressions of my trauma.

I had one such revelation when I presented my sculpture Exquisite Tension (see Figure 4) for feedback. The work had been made intuitively, with the intention of exploring the contrast between delicate, fragile materials and heavy, hard ones. A found rusted steel piece – later revealed to be an old sewage vent – was suspended centimetres off the ground, held up by a thin tube of crochet, its threads straining with the weight of the metal. The crochet component was attached further up to a thick chain, hanging on a hook in the ceiling, which hoisted the entirety of the piece up. Although the feedback session was encouraging and quite successful in itself, the true revelation came afterwards, in conversation with a classmate. As we walked out of the classroom, this person explained to me how they were struck with emotion in front of my work, so much so that they considered leaving the room as they felt the silent creeping sting of approaching tears. The work had evoked in them the heaviness of bearing the burden of too much responsibility at a young age. In the strain of the thread, they remembered the strain of a child being stretched thin. I remembered, too, and realised. The feeling was similar to that of finding a word on the tip of your tongue – that familiar rush of relief. Finally, it all made sense! What I thought had been merely material explorations were far more than that – I had been subconsciously processing my childhood trauma, sculpting the experience of enduring my father’s near-fatal stroke and my mother’s abuse. My consistent use of hard and soft materials, light and dark colours, had been subconscious attempts at bringing together such disparate moments and feelings in my life, allowing innocence and suffering to bleed into each other. In that epiphanic instant, I realised, like American artist Catherine Barrette, that I ‘could deal with my trauma in my art and had been doing so in a way that was veiled even to me’ (2013:174).

Conclusion

Although subject to variation, the aforementioned elements are the most recurrent components that constitute my artistic practice. From unexpected encounters with things from the outside world that touch something in my inner world, to the act of making and intuitively experimenting with materials – all of these instances entail a state of openness within me. Openness to being affected by an object, to the potentialities of a material, to embracing and following changes that may occur. Thus I ‘participate in a flow of process’, as Phillips (2010) describes, in which fumbling is not a blind nor clumsy way of making, but an intuitive and improvisational means for intriguing ideas and works to unfold. I have found, in my experience, that an intuitive and improvisational practice is inherently purposeful in its openness to find, feel, test, discover and express.

Reference List

Barrette C (2013) ‘Trauma: Mourning and Healing Processes Through Artistic Practice’, in Bényei T and Stara A (eds) The Edges of Trauma: Explorations in Visual Art and Literature, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Newcastle upon Tyne, England.

Barry R (2009) ‘Ideas Come out of Objects: In Conversation with Mathieu Copeland’, in Lange-Berndt P (ed) Materiality, MIT Press, Massachusetts, United States.

Bennett J (2010) ‘The Force of Things’, Vibrant Matter: a political ecology of things, Duke University Press, Durham, United States.

Beuys J (1980) Joseph Beuys Interview: Kate Horsfield, Lyn Blumenthal, Neugraphic website, accessed 28 May 2023. http://www.neugraphic.com/beuys/beuys-text5.html

Bolt B (2007) ‘Material Thinking and the Agency of Matter’, Studies in Material Thinking, 1(1):1-4.

Frykman J & Povrzanovic Frykman M (2016) ‘Affect and Material Culture: Perspectives and Strategies’, in Frykman J & Povrzanovic Frykman M (eds) Sensitive Objects: Affect and Material Culture, Kriterium, Sweden.

Nauman B (28 September 2001) ‘Identity’, ART21, ART21 website, accessed 27 May 2023. https://art21.org/watch/art-in-the-twenty-first-century/s1/bruce-nauman-in-identity-segment/

Nin A (1973) The Journals of Anaïs Nin: Volume 1 1931-1934, Quartet Books Limited, London, England.

Pfaff J (8 June 2012) ‘Making and Feeling’, ART21, ART21 website, accessed 27 May 2023. https://art21.org/watch/extended-play/judy-pfaff-making-feeling-short/

Phillips A (2010) ‘Education Aesthetics’, in O’Neill P & Wilson M (eds) Curating and the Educational Turn, De Appel, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Richard E (2020) “Yes, and…”: How Artists Are Using Improvisation and Spontaneity in Their Work, ART21 website, accessed 27 May 2023. https://art21.org/read/yes-and-how-artists-are-using-improvisation-and-spontaneity-in-their-work/

Shouse E (2005) ‘Feeling, Emotion, Affect’, M/C Journal, 8(6), doi:10.5204/mcj.2443.

Sze S (27 July 2012) ‘Improvisation’, ART21, ART21 website, accessed 27 May 2023. https://art21.org/watch/extended-play/sarah-sze-improvisation-short/

Townsend P (2019) ‘The Pre-Sense’, Creative States of Mind: Psychoanalysis and the Artist’s Process, Routledge, England.