Essay by Lucas Jennings for Contextualising Practice

When artists depict other people in their work, there is an imbalanced power dynamic, and critical ethical considerations arise. As my practice demonstrates, the need for ethical consideration becomes imperative when the depicted subject is a deceased person. Through analysing a broad spectrum of ethical theory, this essay will devise a framework that artists can use to responsibly depict their living or dead subjects. Using this framework, I will then re-evaluate a series of works I have created that depict a deceased loved one. This critical reflection will allow me to continue my work in a manner that preserves the dignity and posthumous privacy of my deceased subject.

Whenever another person is the subject of an artwork artistic practice is permeated by the need for ethical considerations. As Bal has noted ethics is the ‘…the development of, awareness of and compliance with general norms of what is right or wrong’ (Bal 2017:37). The power imbalance, or possibility of challenging norms of right and wrong, materialises in portraiture as the artist is exerting their will over the subject’s likeness (Bell 2019). Through the depiction of their subject, an artist will create an impression of a person that can either praise or criticise, flatter or humiliate, empower or objectify (Eaton 2017; Bell 2019). This power must be used responsibly by artists, regardless of the subject’s level of involvement in the process, as a lack of ethical consideration is self-serving and may have harmful effects on the people depicted.

In Respecting Photographic Subjects, Macalester Bell (2019) examines Nussenzweig v. diCorcia, a legal case resulting from an artist’s failure to consider the power imbalance within the portraiture process. Unknowing photographic subject Erno Nussenzweig sued photographer Philip-Lorca diCorcia upon learning that a portrait of him had been taken while publicly walking in Times Square years prior. A part of his Heads series, diCorcia obtained the portrait from a long-lensed camera obscured by construction work and a strobe light, which would photograph passers-by. Nussenzweig’s portrait was exhibited in galleries around the world and sold in a limited edition between $20,000 – $30,000 each. While Nussenzweig stated the portrait infringed on his religious freedom as an orthodox Jew and that it violated his privacy, the New York Supreme Court ruled in favour of diCorcia (Gefter 2006), upholding the portrait as artistic expression under the First Amendment. Bell writes that while diCorcia was legally within his rights to produce, exhibit and sell the portraits, his deceptive methods of obtaining them demonstrates a lack of respect for his subjects and constitutes a moral failing.

Guidelines for how artists should depict their subjects are limited. However, the existing literature highlights several considerations artists can make to work ethically. Chief amongst these considerations is, according to Bell (2019), the granting of informed consent regarding how their likeness will be depicted and in what context it will be exhibited . Artists should also be open to collaborating with their subjects, incorporating their input into how they are depicted in the artwork (Danto 2007; Bell 2019). Of course, the artist should not be beholden to the desires of their participant, but as Bell (2019) explains, if one wants to conduct an ethical practice, a compromise between the free expression of the artist and the rights of the subject must be reached. As Assmann (2017) asserts in this collaboration, an atmosphere of empathy must first be established between practitioner and subject before the work can move forward. This assists the participant to open up to vulnerable positions that the work may place them in. Artists ought not to exploit their subjects by causing harm to them in the name of their art. For example, Jill Greenberg’s End Times series, containing close-up photographs of young children crying, caused a moral backlash due to how the series was made (Eaton 2017). While Greenberg claimed the provocation of their child models was tame, critics lambasted Greenberg for capitalising off the deliberate distress they caused and declared the series morally questionable. For artists to work ethically, they must foster an atmosphere of empathy by respecting the dignity of their subjects and by having the humility to relinquish their authorial power by collaborating with them. Making these considerations will prevent exploitative power imbalances from occurring.

When an artist is depicting a deceased subject within their work, the ethical dilemmas they face require more consideration than when the participant is living. As Ellis (2007) has noted the dead cannot consent to the use of their likeness, cannot collaborate with the artist, and can offer no input regarding their depiction. In instances such as these, the artist has absolute power and must act responsibly, as harm can still be done to the deceased subject. While, as Tomasini (2017) as argued, there is philosophic debate as to if the dead can in fact be harmed, the consensus within the scientific community is that harm can be done to the dead by violating their dignity or acting against their posthumous wishes (De Beats 2004; Caswell and Turner 2021). Artists who wish to ethically depict deceased subjects must not only be aware of this increased power imbalance, but also of the context sensitive instances in which their work may posthumously harm the subject.

Research into how artists may ethically portray deceased subjects is limited. However, inspiration can be taken from the ethical frameworks used in sociological research and scientific fields that concern the deceased. In A Declaration of the Responsibilities of Present Generations Towards Past Generations, historian Antoon De Beats (2004) writes that the dead occupy a space between object and organism. As they are no longer autonomous beings, they are not granted the same human rights afforded to the living. However, they retain elements of their former selves and should thus be treated with respect and dignity (De Beats 2004), particularly as they are now perpetually suspended in a vulnerable state. Despite their depleted agency, as Caswell and Turner (2021) articulate, the dead can still possess abstract goods such as their reputation and the desire for privacy. Preserving the subject’s dignity means not depicting them in a manner which would be interpreted as disrespectful, derogatory or as capitalising on the passing of the deceased (Öhman and Floridi 2018). To ensure that they are safeguarding the dignity of the deceased subject and not violating their privacy, it is best for artists to consult the surviving relatives of the deceased to seek their approval and guidance (Ellis 2007; Tomasini 2009). If such consultation is not possible, then it is recommended to treat the deceased as if they were still alive and not reveal any information about them that would be inappropriate while still living. In revealing information about a dead subject, the artist must evaluate whether the violation of the deceased’s privacy is justified by the public interest that the artwork would generate (Caswell and Turner 2021). Often this is not the case and more ethical methods, Crossen-White (2015) suggests, should be utalised such as anonymising the subject, using a pseudonym, altering their likeness, or fictionalising aspects of the. All these methods strike a balance between exploring the subject matter and respecting the deceased person. Through examining a broader field of study, artists can source guidance for how best to navigate the abundant ethical dilemmas that arise when depicting the deceased.

This specific field of ethical study is highly relevant to my artistic practice, as my work frequently references a deceased loved one. In accordance with the ethical considerations, I outlined earlier, I shall be anonymising my deceased subject in an attempt to preserve their posthumous privacy. I would be remiss, however, if I did not divulge certain details about their passing that are contextually relevant for the artworks being discussed. For ease of communication, I will be referring to my deceased loved one with the pseudonym of Ted. Ted died in 2018 while home alone after tripping and breaking his already damaged neck. They had a history of mental illness and were an extremely private person, a preference that could often become outright paranoia. Ted lived alone, separated from their small network of family and friends. It was a lonely and unceremonious death as they perished on the cold, hard tile floor. My grief regarding Ted’s death and the solitary nature of it has fuelled my practice since the event took place. While I have only recently become aware of the ethical considerations that an artist ought to take when depicting a deceased subject, knowing Ted as an extremely private person prevented me from exploiting the imbalanced power I have over them as a subject. Revaluating my past work will reveal whether I have worked ethically or taken advantage of my subject.

When instructing students on how to ethically discuss the stories of the deceased, communication scholar Carolyn Ellis (2007:25) warns that, ‘intimate, identifiable others deserve at least as much consideration as strangers and probably more.’ This certainly reflects my experience in depicting Ted in art. Knowing Ted’s preference for privacy influenced how I made work about them. Instead of depicting their likeness in a realistic manner, I opted for a more subtle, abstract approach. The paintings Volume 15: Stumbling (2021) and Volume 18: Home Alone (2021) were produced concurrently as the first works I made in response to Ted’s death. Volume 15: Stumbling (see Figure 1) recounts my own experience of witnessing Ted’s decline due to mental illness, while Volume 18: Home Alone (see Figure 2) is a representation of Ted’s solitary demise. Materiality is a focus of these works with the sewn elements representing the tangible and organic while paint represents the inanimate. In Volume 15 the black form is completely sewn into the canvas but in Volume 18 the form is dissipating. Life flows out of its body onto the cold floor, rendering the figure naught but a lifeless blob of paint. By assuming Ted’s desire for posthumous privacy and then by respecting said desire, I feel I have avoided exploiting him as an unconsenting artistic subject. Inspiration from Ted’s life was taken for the paintings while his likeness and other identifiable details were obscured. Although the artworks were briefly exhibited publicly and available for purchase, I do not feel this constitutes questionable commercialisation of Ted’s passing as this was based solely on the aesthetic merits of the paintings and not on the subject who was an obscured agent. Upon revaluating these works years later, I feel they fall within the bounds of ethical practice as they neither violate the privacy nor dignity of the deceased subject.

Recently, I have moved away from the sombre subject matter of Ted’s untimely death and am instead trying to depict them in a more positive fashion. This desire is what drew me to the methodology of contemporary Australian artist Julia Gutman. Gutman’s work depicts her own friends and family in large, embroidered textile work (Wilson 2022). These works are built from clothing donations she receives from her friends and family (Wolifson 2020). During the creative process, she takes her subject’s input into how they should be depicted and incorporates their feedback into the artwork. This model of ethical collaboration produces work that is authentic to the characters of those depicted and was precisely what I was hoping to accomplish.

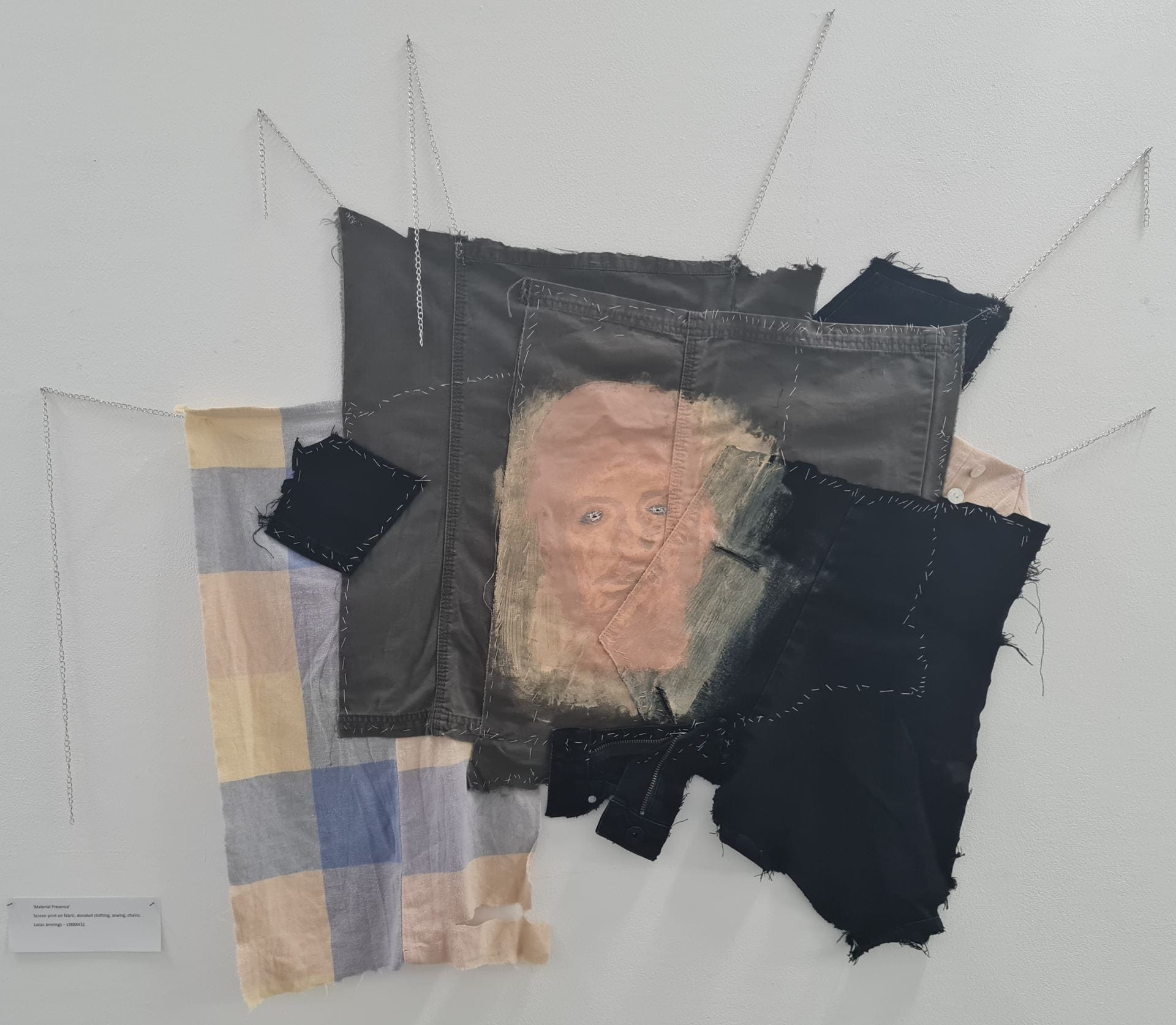

My inspiration from Gutman’s ethical practice resulted in the piece titled, Material Presence (2023). Following Gutman, I accepted clothing donations from Ted’s family (including myself), tore them up and sewed them back together into a crude canvas that I screen printed his likeness onto. However, the uneven surface of the fabric prevented the screen from printing with the intended photographic level of quality I had initially intended. I initially disliked this result but quickly warmed to it upon realising that an obscured likeness would be more in line with Ted’s preference for privacy. Upon comparing the finished Material Presence (see Figures 3 and 4) to Gutman’s textile works, a troubling dissonance occurred to me. As Wilson has noted (2022) Gutman’s figures stand together in ‘a collective spirit, one based on the desire for community, tenderness, and friendship between women’, while my figure remained alone within a black void. I felt I had failed to do justice to Ted’s memory until a family member reassured me that Ted was indeed a solitary person and that was not an inherently negative quality.

My current studio endeavours have been completely upended by ethical dilemmas that have arisen due to my intended depiction of a deceased subject. In my initially proposed project, I intended to produce a double-sided doll, made from screen printed fabric. The front facing side of the doll would depict a camp, flamboyant character in the style of 1960’s American comic book supervillain while the reverse would depict the civilian identity of this villain – an unconfident middle-aged man. The project would explore the history of queer-coded villains in the comic book medium as well as notions of repressed identity. Inspiration would be taken from Ted’s life, referencing petty crimes he committed and his identity as a closeted bisexual man. In continuing with this initial project, I would be outing a dead man with no justification other than personal gain, violating his posthumous privacy in the process.

Outing a queer person, as Gross (1991) notes, is typically considered a dirty tactic, designed to illicit shame in the outed individual. Unless the individual being outed has some relevant history of hypocrisy towards the queer community, outing is not considered within the field of public interest (Tandoc and Jenkins 2018). The outing of private individuals with no history of anti-queer rhetoric is unjustifiable. According to Tandoc and Jenkins (2018), ‘the truth does not automatically merit publication.’

Realistically speaking, Ted was an anonymous figure and posthumously outing him would have no real impact on his reputation. Our family corroborated this notion and granted me consent to use this information as I please. As Ted’s closest living relative I felt entitled to tell his story, feeling I was the only one who could responsibly do so. However, as Ellis argues (2007), familial connection alone does not justify the public revelation of another’s private life and to do so would be immoral. The narrative of repressed queer identity in the project has been minimised and connections to Ted have been anonymised to safeguard his privacy. While I may return to the subject matter of Ted’s repressed identity, future projects will do so in a manner that respects his right, even in death, to self-determination.

Through studying a broad field of ethical frameworks, I have established a guideline that will assist artists, and myself, in depicting human subjects our work, whether living or dead. Following these guidelines will prevent artists from exploiting power imbalances that arise when working with a subject. Revaluating my past and current work through these ethical guidelines has prevented me from exploiting my deceased loved one. As I continue practicing art at an increasingly professional and public level, continuing to follow these considerations will maintain my ethical integrity.

Reference List

Assmann A (2017) ‘The Empathetic Listener and the Ethics of Storytelling’, in Meretoja H and Davis C (eds) Storytelling and Ethics: Literature, Visual Arts and the Power of Narrative, Routledge, New York.

Bal M (2017) ‘Is There an Ethics to Story-Telling?’, in Meretoja H and Davis C (eds) Storytelling and Ethics: Literature, Visual Arts and the Power of Narrative, Routledge, New York.

Bell M (2019) ‘Respecting Photographic Subjects’, in Maes H (ed), Portraits and Philosophy, Routledge, New York.

Caswell G and Turner N (2021) ‘Ethical challenges in researching and telling the stories of recently deceased people’, Research Ethics, 17(2):162-175, doi:10.1177/1747016120952503.

Crossen-White HL (2015) ‘Using digital archives in historical research: What are the ethical concerns for a ‘forgotten’ individual?’, Research Ethics, 11(2):108-119, doi:10.1177/1747016115581724.

Danto AC (2007) ‘The Naked Truth’, in Walden S (ed), Photography and Philosophy: Essays on the Pencil of Nature, Blackwell Publishing, doi:10.1002/9780470696651.ch13.

De Beats A (2004) ‘A Declaration of the Responsibilities of Present Generations Towards Past Generations’, History and Theory, 43(4):130-164, doi:10.1111/j.1468-2303.2004.00302.x.

Eaton AW (2017) ‘The Ethics of Portraiture’, in Meretoja H and Davis C (eds) Storytelling and Ethics: Literature, Visual Arts and the Power of Narrative, Routledge, New York.

Ellis C (2007) ‘Telling Secrets, Revealing Lives: Relational Ethics in Research With Intimate Others’, Qualitative Inquiry, 13(1):3-29, doi:10.1177/1077800406294947.

Gefter P (19 March 2006) ‘The Theater of the Street, the Subject of the Photograph’, The New York Times, accessed 15 May 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2006/03/19/arts/design/the-theater-of-the-street-the-subject-of-the-photograph.html

Gross L (1991) ‘The Contested Closet: The Ethics and Politics of Outing’, Critical Studies in Mass Communication, 8(3):352-388, doi:10.1080/15295039109366802.

Öhman C and Floridi L (2018) ‘An Ethical Framework for the Digital Afterlife Industry’, Nature Human Behaviour, 2(5):318-320, doi:10.1038/s41562-018-0335-2.

Tandoc Jr EC and Jenkins J (2018) ‘Out of bounds? How Gawker’s outing a married man fits into the boundaries of journalism’, News Media & Society, 20(2):581-598, doi:10.1177/1461444816665381.

Tomasini F (2009) ‘Is post-mortem harm possible? Understanding death, harm and grief’, Bioethics, 23(8):441-449, doi:10.1111/j.1467-8519.2008.00665.x.

Tomasini F (2017) Remembering and Disremembering the Dead: Posthumous Punishment, Harm and Redemption over Time, Palgrave Macmillan, Leicester, UK.

Wilson EK (2022) In the studio: Julia Gutman, Art Almanac website, accessed 6 May 2023. https://www.art-almanac.com.au/studio-julia-gutman/

Wolifson C (10 November 2020) ‘The tragedy that changed everything for artist Julia Gutman’, Sydney Morning Herald, accessed 7 May 2023. https://www.smh.com.au/culture/art-and-design/the-tragedy-that-changed-everything-for-artist-julia-gutman-20201110-p56d79.html