Essay by Luna Yang for Contextualising Practice

According to Stets and Bourke, structured society imparts values that individuals identify themselves with, which form the basis of one’s identity (2000). As a young adult, when it come to the topic of identity, I felt confused. Being a first-generation immigrant causes a great deal of stress which manifests as not having a clear sense of self. In this essay, I will explore the topics of cultural identity, racism and gender identity and how I utilise painting and drawing to unpack, understand and express the complex and often challenging emotions they evoke for a non-binary first-generation immigrant.

In the work of Stets and Burke (2000), identity is conceptualised as a role that is actively ‘enacted’ and ‘performed’, written about as a performance of self rather than an inherent trait. The performance of identity allows oneself to either be categorised, or actively resist it, which becomes a category of its own. Stets and Burke reinforce that individuals often assign themselves into groups or roles to satisfy their desire for self-worth, personal value, competence, and efficacy. The acceptance of an individual within a group significantly increases their sense of self-worth. In group-based identities, the members of the group are inclined to act in a uniform, homogenous way, and differentiate themselves from the out-group (Stets and Burke, 2000).

In Australia and America, the ethnically dominant group comprises white people, while Asians are a minority (ABS 2021; USCB 2022). Considering this, it can be inferred that there may be similarities in the experience of Asians in America and Australia, although these experiences are not interchangeable. It is challenging to substantiate this claim with a specific source, but it is important to mention that when many people use the term ‘Asians’, they often refer specifically to individuals from East Asian countries. ‘Asians’ in this essay relates to Asians inclusive of East and South-East Asians unless otherwise specified. The term Asia and Asian is inclusive of many countries and I would like to note that I am speaking from an East Asian and Chinese perspective.

Racial microaggressions are intentional and unintentional, brief, and commonplace verbal, behavioural, and environmental actions that convey hostility, derogatory attitudes or negative racial slights and insults towards a person or group (Nadal et al. 2014). In my experience as a first-generation Chinese immigrant, I experience microaggressions in everyday life, yet I choose to ignore them or feign compliance, fearing escalation. Wu (2002) exemplifies that discrimination against Asians can reside in seemingly innocent questions.

‘Where are you from?’ is a question I like answering. ‘Where are you really from?’ is a question I really hate answering… For Asian Americans, the questions frequently come paired like that…. More than anything else that unites us, everyone with an Asian face who lives in America is afflicted by the perpetual foreigner syndrome. We are figuratively and even literally returned to Asia and ejected from America.

In the above quote from Wu (2002) he uses the term ‘perpetual foreigner syndrome’ to narrate his grievances about frequently being questioned of his American identity due to his Asian heritage. Hyunh et al. (2011) utilises the term ‘Perpetual Foreigner Stereotype’ to describe the way in which members of ethnic minority backgrounds are consistently seen as outsiders within the Anglo-Saxon dominant society of the United States.

I am affected by perpetual foreigner syndrome which fractures my sense of identity. I experienced trauma and grief through forced immigration. I immigrated here when I was four without being asked for an opinion. I am glad it happened, though I was faced with the traumatic process of living in a new place, learning a new language and realising different social norms.

I occasionally feel that I am not welcome in Australia due to a range of personal experiences and anecdotal stories from my peers. Blair et al (2017) presents that in a sample size of 6001 residents of all nationalities throughout Australia, 33% of people reported experiencing racism within institutional settings like the workplace and in education. Up to 40% of participants reported experiencing ‘everyday racism,’ occurring in public spaces through disrespectful behaviour, mistrust, or name-calling. This is not to say that all Australians are racist, but I do not feel a sense of belonging, loyalty, or nationalism to Australia.

I do not particularly identify with other Chinese migrants in Australia either, because my Chinese is simply not good enough; I have not been taught complex conversational Mandarin and the myriad of slang that exists in the modern-day Chinese language. I have been called ‘whitewashed’ on at least two occasions by other East Asian people. What they mean is that I don’t look, live, or act in a way that is ‘Asian’ enough for them. This is very harmful as there is no specific way that East Asians look or act outside of stereotypes. On the few occasions I have visited my family in China, I felt like a tourist and an outsider, as I only lived in China until I was four. I could read most of the Chinese around me, but my conversational skills were lacking. As I was chatting with my sisters in English, I felt strangers’ eyes on us because of our Chinese faces and fluent English. We stood out.

To summarise, I stand apart from the ethnic majority in Australia due to my Chinese heritage. Although I am a first-generation Chinese immigrant myself, my extended stay in this country has created a sense of detachment from those who have recently arrived. Paradoxically, I feel like an outsider when visiting my home country. This dilemma has caused periods of crisis, confusion, and depression throughout my life, regularly leading to the question – Who am I?!?!?

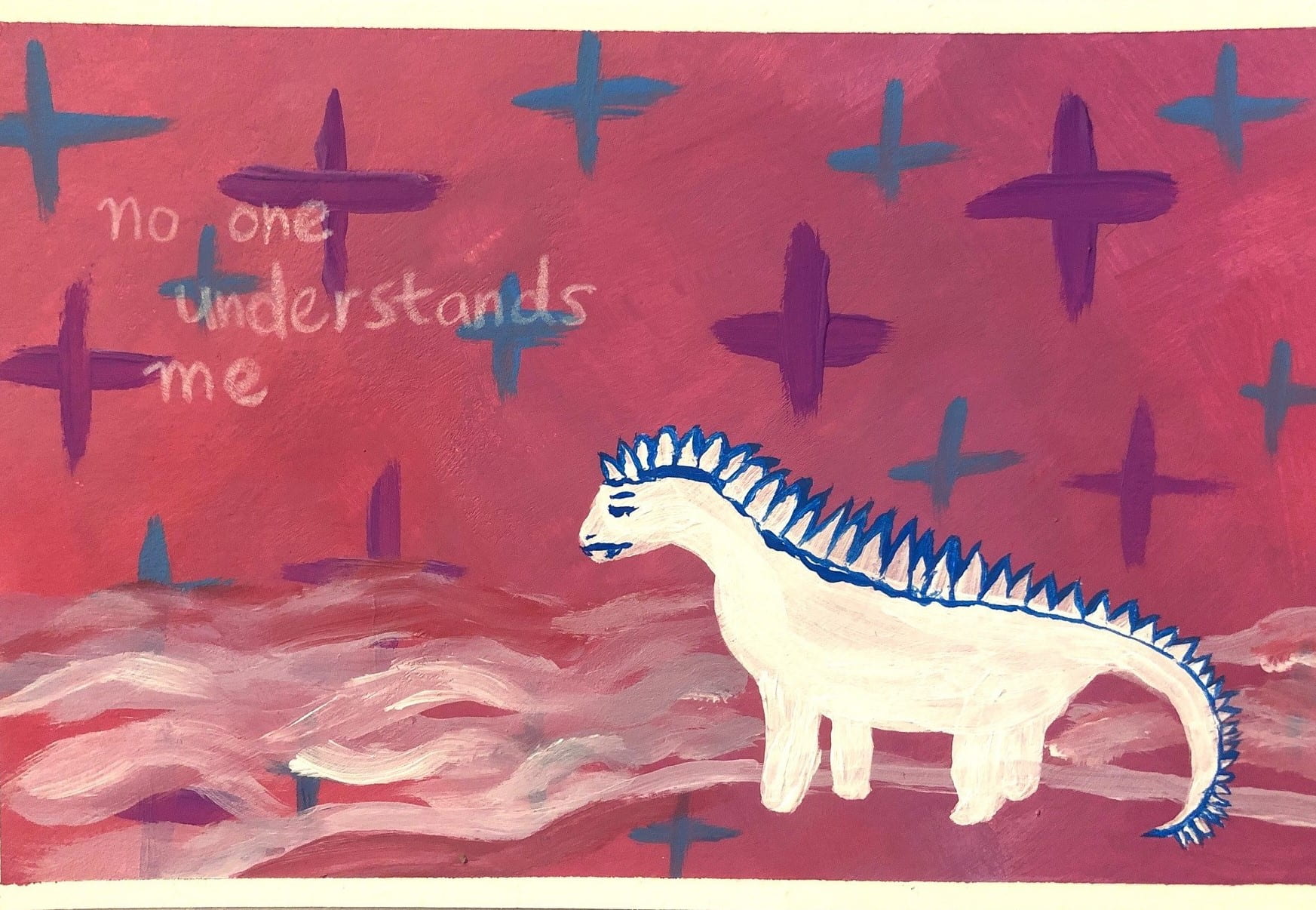

I explore the painful feelings caused by my identity crisis in my diptych Dinosaur Thoughts, comprised of two postcard-sized acrylic paintings on paper. Each features a white dinosaur with spikey blue outlined osteoderms (scales on the spine of a dinosaur). There are red, blue, and purple plus (+) symbols that litter the sky and are behind the details of the foreground in both works. The first work consists of a dinosaur with an ambivalent expression standing to the left, looking towards the right. There is a background of blue mountains with black grass in the foreground. Text in white coloured pencil reads ‘I don’t want to exist’. The second work features a pink background, and a sullen-faced dinosaur is standing on a patch of land to the right of the piece, facing left. It is surrounded by white coloured waves that blend into the horizon, with white text reading ‘no one understands me’. A white border is incorporated into the top and bottom edges of the work. The figures mirror each other in the space and the horizon lines blend into one.

The lone dinosaurs, along with the text, convey the grief and sorrow that I have experienced through the process of growing up in an unfamiliar country. My feelings of alienation are narrated by the words ‘no one understands me’ and the image of an upset-looking creature. The white colour of the dinosaurs represents a blank slate, a fog that is my identity. I have utilised contrasting colours to exemplify the experience of being a foreigner. The dinosaurs in the image do not blend into the background, the outlined figures stand out sharply, representative of my feelings of not fitting in as an Asian Australian.

The anthropomorphic dinosaur thinking negative thoughts is my way of distancing myself from my thoughts, reminding myself that thoughts are not fact. These artworks allow me to have hope that I can and will resolve my identity crisis in time. The plus signs in the background are stars. The comfort of twinkling stars radiates hope, plus signs symbolise positivity in the face of adversity. I wanted to remind myself that even though I may feel insecurity and pain, there are still many positive people and things to look forward to. The colours blue and pink serve as an investigation into my gender identity.

I identify as non-binary. I was socialised as a female, and I present myself in a more feminine way. Because I have long hair and feminine features, it is assumed that my gender is female. It does not bother me. What bothers me is that I feel obliged to present femininely because of my homophobic and transphobic family that I cannot come out to. Being socialised as a woman has influenced my identity and my view of the world. I have at times stared into the mirror at my reflection, contemplating who I am, and wondering where I fit into the narrative of our world.

Attané and Guill (2012) magnifies that women are far from socially equal in Chinese society, though there have been improvements since the 1950’s. Gendered roles permeate the private home life, where women spend two-and-a-half to three times the amount of time on domestic tasks when compared to men. Male children are seen as more valuable than female children as they are the ones who continue the family name (Attané and Guill, 2012). Female babies face a higher mortality rate than male infants, due to lower vaccination rates and longer delays in bringing them to medical attention.

Ibrahim (1992) recognises that Asian-American women emerged in the west as ‘nameless, faceless, alien members (1992:49)’ of society and categorised as sexually subservient. Ibrahim (1992) communicates that Asian Americans face a double bind, where they feel obliged to preserve their ethnic identity due to Eastern familial values yet are oppressed and discriminated against by western society for those same values. Asian women are encouraged to be ‘good girls or women (Ibrahim 1992:50)’ by pursuing standards of behaviour set by Asian society and their parents.

I have been instructed by my parents, my mum in particular, on how to live my life in a variety of ways; my mum continues to provide me with instructions about diet, beauty, and studies that I don’t always choose to follow. I have embraced the feminine side of myself whilst rejecting the masculine because I am praised when I am a beautiful, pretty girl. The repression of my gender identity for my entire life has caused confusion, depression, and a variety of emotions that I do not know how to handle.

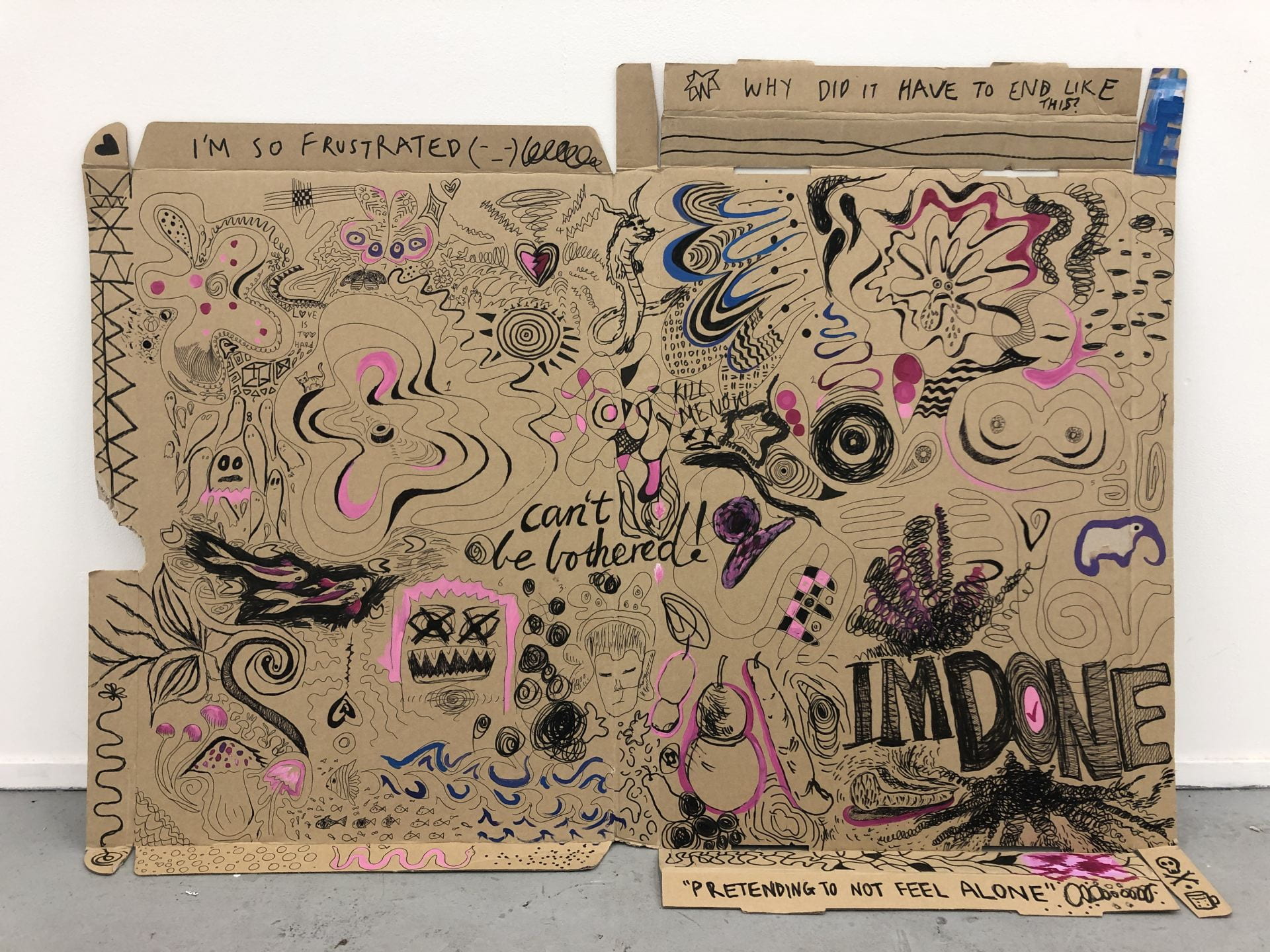

In my work Cardboard Drawings, I attempt to draw my feelings onto the great cardboard canvas. It consists of a found cardboard box, one-and-a-half metres long and one metre high. It is rectangular in size, and the connecting flaps are visible. Most of the cardboard is covered in ink drawings of a range of subject matter with parts coloured in pink, blue, and purple. Cursive text that reads ‘can’t be bothered’ and another ‘I’M DONE’. Some of the things I have drawn include abstract linework of a woman’s head and nude body, an angry square face with its eyes crossed out, curved shapes resembling flowers, and dark spirals.

Cardboard is a cheap commodity that people use for packing things. It exists to protect and label the items inside. The cardboard has become a metaphorical shield to protect me against the outside forces that attack my non-binary gender identity. Through the diverse range of subject matter, I am signalling the many aspects of my identity that exist simultaneously. I utilise the cardboard canvas as a safe space to embrace both femininity and masculinity. The nude woman is one of the drawings in which I embrace my female form. I acknowledge that I was born in a female body, and I appreciate all its parts. The elephant next to it is a symbol of my masculinity, the elephant’s trunk being akin to the phallus.

The uncoloured cardboard and black ink represent that ultimately, I choose not to identify with the gender binary. However, I have created a safe space, a box, for exploring the gender binary. Pink and blue are commonly associated with boys and girls. I have incorporated these colours and purple, the colour I get when I mix the two. I have been influenced by masculinity, femininity, as well as in-between feelings. Much of the work features waves, irregular shapes, patterns, sharp and soft lines. These drawings are a representation of myself, as my gender identity is in flux, malleable, and unique.

The search for identity is a driving force in my artistic practice. I express my deep emotions about not fitting in as a Chinese-Australian immigrant in my work Dinosaur Thoughts. I use Cardboard Drawings as a safe space to explore my gender identity. I convey my changing and evolving identity and gender identity through my art. I will continue to grow my sense of self, challenging notions of gender; I will not give up!

Reference List

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics (2021) Snapshot of Australia, Australian Bureau of Statistics, accessed 13 June 2023. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people-and-communities/snapshot-australia/latest-release#population

Attané I, and Guill E (2012) ‘Being a Woman in China Today: A Demography of Gender.’ China Perspectives, 4(92):5–15, accessed 18 September 2023, JSTOR database.

Blair K, Dunn K, Kamp A and Oishee A (2017) Challenging Racism Project: 2015-16 National Survey Report, Western Sydney University website, accessed 1 September 2023. https://www.westernsydney.edu.au/challengingracism/challenging_racism_project/our_research/face_up_to_racism_2015-16_national_survey

Barbee H and Schrock D (2019) ‘Un/gendering Social Selves: How Nonbinary People Navigate and Experience a Binarily Gendered World’, Sociological Forum, 34(3):572-593, accessed 14 June 2023, JSTOR database.

Darwin H (2017) ‘Doing Gender Beyond the Binary: A Virtual Ethnography’, Symbolic Interaction, 40(3):317-334, accessed 14 June 2023, JSTOR database.

Dunn (18-20 February 2003) ‘Racism in Australia: findings of a survey on racist attitudes and experiences of racism’ [conference presentation], The Challenges of Immigration and Integration in the European Union and Australia, Sydney, accessed 13 June 2023. https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/handle/1885/41761

Elias A, Mansouri F, and Paradies Y (2021) Racism in Australia Today, Palgrave Macmillan Singapore, doi:10.1007/978-981-16-2137-6.

Hua Z and Wei L (2016) ‘“Where are you really from?”: Nationality and Ethnicity Talk (NET) in everyday interactions’, Applied Linguistics Review 7(4):449-470, doi:10.1515/applirev-2016-0020.

Huynh QL, Devos T, and Smalarz L (2011) ‘Perpetual Foreigner in One’s Own Land: Potential Implication for Identity and Psychological Adjustment’, J Soc Clin Psychol, 30(2):133-16, doi: 10.1521/jscp.2011.30.2.133.

Ibrahim FA (1992) ‘A Course on Asian-American Women: Identity Development Issues’, Women’s Studies Quarterly, 20(1/2):41-58, accessed 13 June 2023, JSTOR database.

Lacapra D (2016) ‘Trauma, History, Memory, Identity: What Remains?’, 55(3):375-400, accessed 14 June 2023, JSTOR database.

Nadal KL, Griffin KE, Wong Y, Hamit S, and Rasmus M (2014) ‘The Impact of Racial Microaggressions on Mental Health: Counseling Implications for Clients of Color’, Journal of Counseling & Development, 92(1):57-66, accessed 13 June 2023, Wiley Online Library database.

Stets JE and Burke PJ (2000) ‘Identity Theory and Social Identity Theory’, Social Psychology Quarterly, 63(3):224-237, accessed 13 June 2023, JSTOR database.

USCB (United States Census Bureau) (2022) QuickFacts United States, United States Census Bureau, accessed 13 June 2023. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045222

Wu F (2002) ‘Where are you really from? Asian Americans and the perpetual foreigner syndrome’, Civil Rights Journal 6(1):14, accessed 13 June 2023, Gale Academic Onefile database.