Essay by Ka Yan So (Kelly) for Contextualising Practice

The artist transforms the personal into the universal, creating an object that can be experienced and felt by others, that has the power to move and inspire. (Townsend 2019)

Creating installation artwork has become the central focus of my artistic practice, allowing me to express the emotional triggers associated with my personal trauma. A profound moment occurred when I witnessed a stranger burst into tears while experiencing my installation piece, titled Love & Pain, Pain & Love (2022). This essay will argue, through analysis of my practice, that installation art possesses great affective power. Even the slightest trace, a single object, within the space can serve as a transitional object, enabling viewers to emotionally engage with the artwork, to fell ‘with’ the artwork. This effect is particularly pronounced when the installation delves into the exploration of trauma. In this essay, I aim to delve into my installation artworks My Bed (2022) and Love & Pain, Pain & Love (2022), to discuss how the selection of objects and the creation of an immersive space work together to construct a transitional object, enabling viewers to confront personal trauma in both physical and psychological dimensions.

To understand how viewers engage with my installation artwork, it is crucial to define the concept of ‘Transitional Object’. According to the psychoanalyst and pediatrician Donald Winnicott, infants often select soft objects like blankets, imbuing them with symbolic representations of their mother’s nurturing presence. These transitional objects serve as tangible sources of comfort, providing a sense of familiarity and continuity. They also act as bridges, facilitating an interplay between the infant’s internal and external realities, allowing them to explore the past and present through imaginative play (Winnicott 1953). When applied to the realm of art, artists similarly choose materials from the external world that evoke a sense of intimacy, recognising their potential to be transformed into expressions of personal experiences (Townsend 2019). This transformation can then become a transitional object for viewers, inviting them to resonate with their own personal histories.

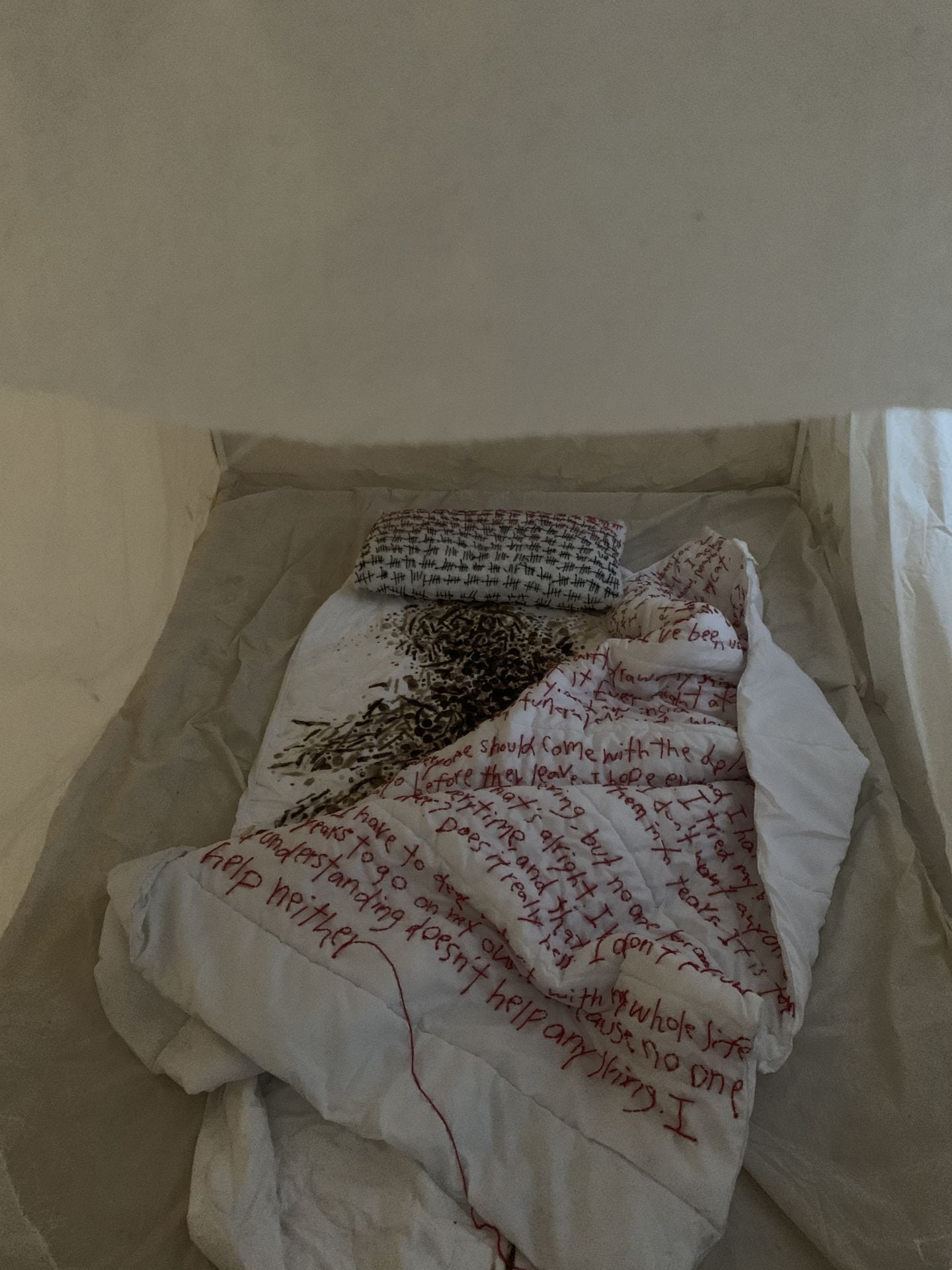

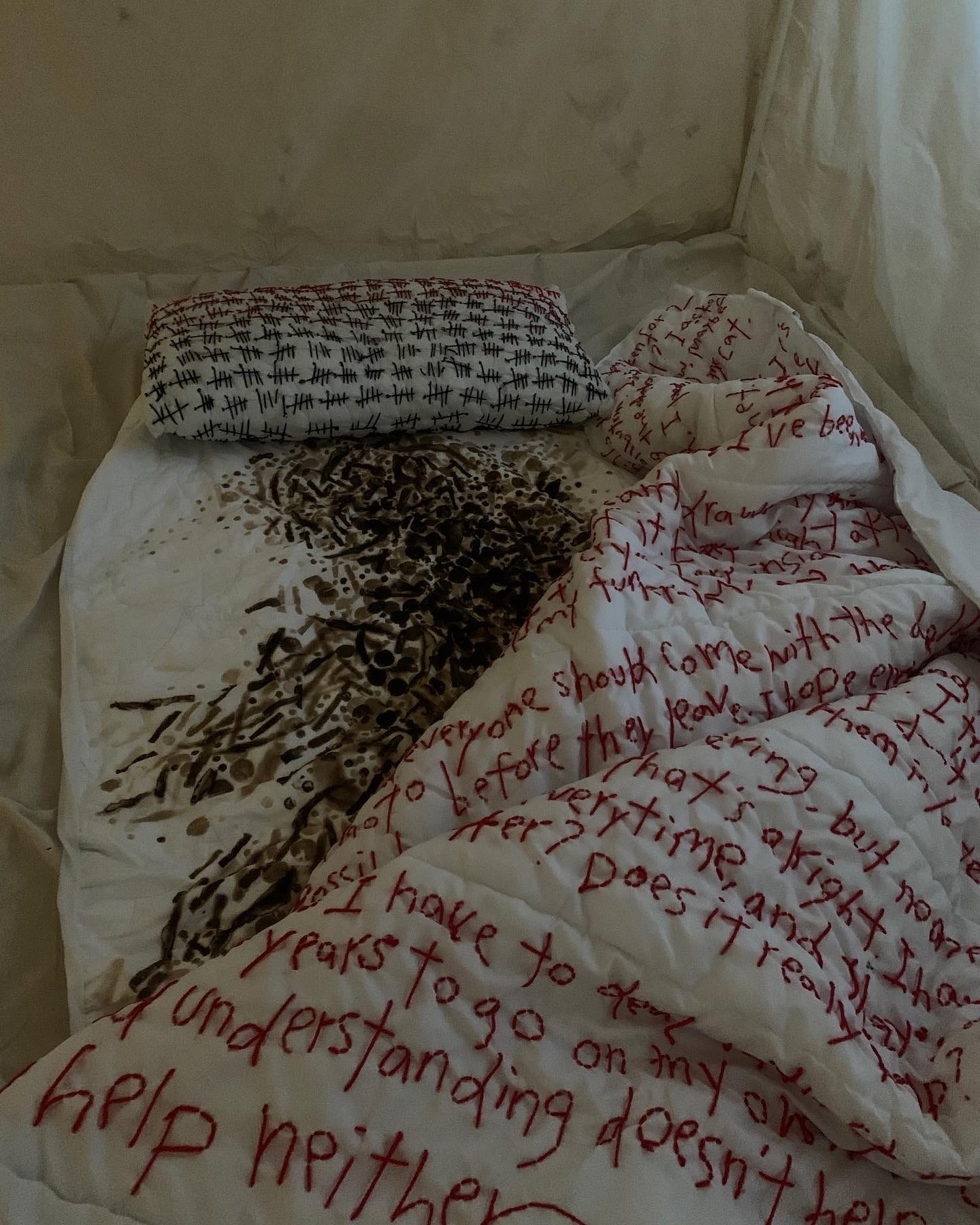

Drawing inspiration from Winnicott’s theory of transitional objects, my first installation artwork My Bed (2022) serves as a tangible artistic expression of my personal traumas. It emerged during a challenging period in early 2022 when I embarked on a journey to Australia, leaving behind my hometown and confronting intensified depressive disorder and ongoing medication. The emotional weight of bidding farewell to my mother over the phone and the unsettling sensations experienced within the confines of my bed became the catalysts for creating My Bed.

By utilising found objects such as a mattress topper, quilt, and pillow, I transformed my traumas into symbolic artifacts. These objects, infused with my emotions and personal experiences, parallel the soft objects chosen by infants as transitional objects for comfort and security. Through careful reconstruction, visual and tactile cues emerged, including the red-stitched threads on the pillow marking the days of antidepressant pill consumption, the quilt adorned with stitched suicidal writings, and the burn marks shaped in a human figure on the mattress topper. Not only do these cues embody my trauma, but they also invite viewers to explore their own emotions. By transforming familiar domestic objects into vessels of storytelling, the boundaries between my personal history and the artwork dissolve, creating an intimate and transformative space. Within this space, viewers can understand and connect with the shared experience of trauma and potentially relate it to their own lives. By infusing everyday objects with personal history, a sense of familiarity arises, allowing us to, as Bennett has articulated, ‘decode one trauma through another’ (2005), deepening our collective understanding of the human experience.

Every night after saying goodnight to my mum, I started to cry and cry and cry inside my bed. Last night I was thinking about how my funeral is gonna be… I feel pain most of the time, and I am stuck inside my tiny room. I disliked everything I loved, and they became air inside my room. I don’t want anyone to cry for me, so I ate all my thoughts into my stomach and turned them into tears. It’s painful, tough, tiring, suffering, but no one will know. All I know is I must deal with it with my whole life alone.

The sensory experience from the reconstruction of objects plays a pivotal role in physically building affective encounters between the audience and my trauma. In My Bed (2022), the objects themselves become conduits for tangible expressions of emotion, engaging multiple senses and intensifying the viewer’s connection to my experiences. The scent of burnt materials emanating from the mattress topper, combined with the visual imagery of bloody crochet on the quilt and pillow, create a strong sensory experience that evokes a visceral response in the viewer. By specifically placing the objects in the confined space of a handmade fabric room, it generates a palpable atmosphere of suppressed emotions. Additionally, the deliberate construction of the room at my height further enhances the viewer’s immersion into my perspective and intensifies their emotional engagement. Through the enforcement of physically bending their body and adopting my vantage point, the viewer is compelled to confront the traumatic scene directly, heightening their empathic connection with my experiences.

In Empathic Vision (2005) Bennet observed that the positioning of a viewer is important to how and when evocative visual imagery trigger effective responses. As the viewer walks into the fabric room of My Bed and becomes enveloped in its sensory elements, they are not merely spectators but active participants in the narrative. The narrative scenario traps the viewer’s senses, drawing them both physically and psychologically into my personal story. By authentically and physically portraying my trauma, a bond is established between the viewer and the artwork, tapping into the shared human experience of negative emotions. Like artist Tracey Emin’s work My Bed (1999), which boldly exposed her personal life to the public by bringing her dishevelled bed and surrounding objects into galleries, (Tate 2015) my work transforms vulnerability into a tangible experience, which invites viewers to imagine, empathise, and resonate with that pain. Embracing the aesthetic rendering of tangible objects and the detailed depiction of trauma, my artwork prompts the audience to explore my history in an affective and physical manner. By integrating the viewer’s affective response into the artwork, a powerful connection is created, facilitating an exploration of my personal narrative and inviting reflection on the broader human condition.

A group of inactive people in the space of a Happening is just dead space (Kaprow 1966, p.195)

The embodiment of my trauma in the installation artwork My Bed (2022) saw me create an immersive space that the audience could psychologically and physically engage with. Writer Werner (2020:149) asserts that space possesses a dynamic and transformative character, capable of housing memories and evoking emotional responses. This concept strongly influenced my second installation piece, Love & Pain, Pain & Love (2022), which places significant emphasis on the principles of ‘Total Art Theory’. According to Notes on the Creation of a Total Art (1958), Total Art incorporates elements such as light, sound, material, colour inside a space to create an immersive artistic experience (Kaprow 1958). It argues that the art object is no longer the sole focus, but the contextualization of space is part of the artistic expression in installation art.

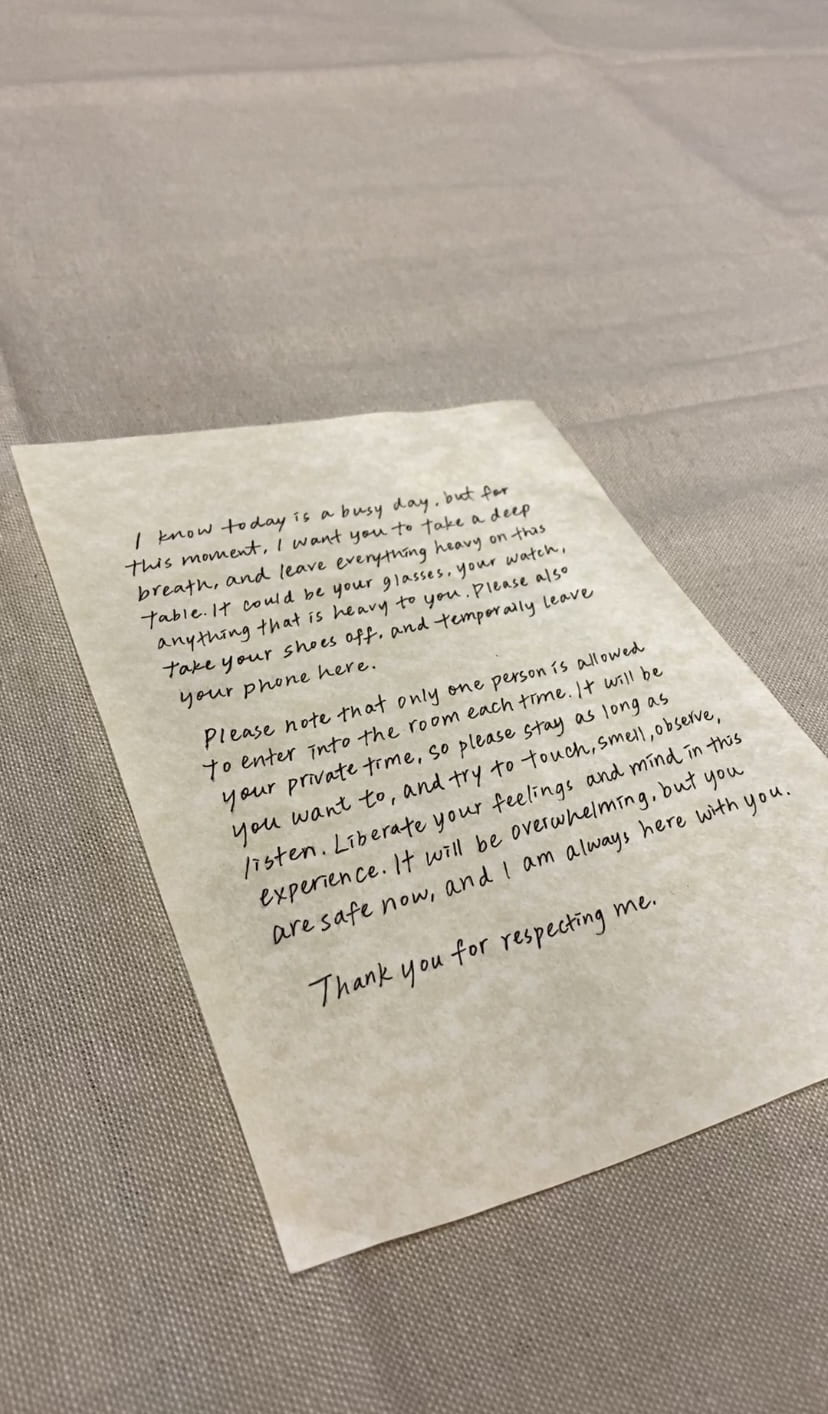

In Love & Pain, Pain & Love, the viewer’s encounter with the artwork is carefully choreographed, beginning with their movement between two distinct spaces separated by a substantial curtain. As seen in Figure 5, they encounter instructions directing them to leave their ‘heavy’ belongings on a nearby table and to remove their shoes, symbolically shedding their own identities and concerns while entering my personal realm. The deliberate transition sets the stage for their immersion into my personal realm, enabling them to concentrate solely on the artwork. After stepping into the distinguished space, the intentional engagement of the audience within the physical space is showcased. A visually arresting and nostalgic human-sized wooden box is positioned at the end of the room. Designed to perfectly contain a single person at a height of two meters, with a length of one meter and a width of just over half a meter, the box creates an intriguing visual and spatial experience. As they approach the wooden box individually, the entire space becomes enveloped in darkness, with the only source of light emanating from the gap in the box’s door. This symbolic invitation entices the viewer to step inside, further deepening their engagement with the artwork.

Moreover, every feature of the spatial arrangement, including lighting, shadow, colour, scent, distance, emptiness, darkness, and individuality, has been orchestrated to elicit a deeply sensorial experience and facilitate the viewer’s emotional comprehension. The contextualisation of the space extends beyond staging (Gronau 2019); it serves as a reflective backdrop for my trauma that prompts viewers to piece together subtle signs and contemplate the significance embedded within the artwork. For instance, the act of compelling viewers to hold their gaze upon the luminous globe and read the confessional writing inside the box evokes the challenges and complexities of confronting my vulnerable emotions surrounding my mother. The encouraged participation places a responsibility on the viewer to explore the intricate details within the expansive space without explicit guidance, thereby fostering imaginative exploration and deepening their understanding of my trauma.

By carefully orchestrating the viewer’s physical and sensory experience, Love & Pain, Pain & Love guides them through a transformative journey. This unique experience and intimate connection with the spatial environment allow viewers to establish personal connections, and draw upon their own memories and emotions, extending the experience beyond the exploration of my specific history. Most importantly, the artwork provides a private and secure sanctuary in which viewers can freely express their own emotions, engendering a powerful and cathartic encounter with the artwork.

The value of an artwork lies in its intertwining of outer and inner worlds, and that its making involves a continuous movement between the two. (Townsend 2019)

Through the sensory experience of trauma within an immersive space, viewers establish a subjective rapport with the artwork, delving into an elusive realm that encapsulates their memories of the past, present, and future. Building upon Winnicott’s theory of the transitional object, psychoanalyst Christopher Bollas introduces the concept of the ‘aesthetic moment’ to elucidate the transformative nature of this experience. According to Bollas (1978), encountering an aesthetic moment transports individuals into an internal space of crystallized time, where they subjectively engage with a transitional object from the external world. This interaction evokes a profound sense of nostalgia, reverie, and compels them to pursue their resurfacing memories. In the case of Love & Pain, Pain & Love (2022), the artwork elicited heightened emotional responses from the audience, particularly in relation to their own maternal relationships. The melancholic atmosphere within the immersive space recalibrated the viewers’ subjectivity, immersing them in an aesthetic moment characterized by an intense search for personal memories that resonated with the artwork.

Articulating the power of melancholy, Brady and Haapala (2003) discuss it as an aesthetic emotion, highlighting its ability to encompass both displeasurable and pleasurable feelings. When confronted with a melancholic artwork that resonates with their own longing and triggers memories, viewers undergo an aesthetic moment where negative emotions associated with trauma, converge with positive emotions tied to nostalgic recollections of joyful moments. In the context of Love & Pain, Pain & Love, viewers embark on a rich emotional journey of transformation that is melancholic.

A sombre aura permeates the immersive space through various elements, such as the darkness, the confinement inside the enclosing box, and the directive to read the confessional writing beneath the gleaming globe. These intense components and the contemplative atmosphere within the immersive space remind viewers of negativity and the resonance of trauma. However, beyond the surface-level manifestations, the aesthetic and imaginative considerations within the artwork cultivate a sense of beauty within melancholy. For instance, the interplay of dramatic lighting, the scent of timber wood, and the warm glow of the light, transport viewers into a distinct world detached from reality. This immersive environment encourages viewers to fully engage with the solitude of the atmosphere and establish connections between the artwork and their personal experiences. They delve into their internal world, imaginatively exploring cherished memories and longings. It is within this aesthetic moment that viewers metaphorically introspect within the confessional box of their own memories and engage in a cathartic experience.

In an interview with artist Louise Bourgeois explaining her installation work Spider (1994), Bourgeois states that the work symbolised the ambivalent love for her mother. Despite the initial sense of fear and uncanniness evoked by the spider’s size and black colour, the immersive encounter – you can walk under it – invokes a feeling of being sheltered. This connection resonates with Love & Pain, Pain & Love, as the melancholy within the immersive environment acts as an intermediary between the disquietude of trauma and the yearning for a mother’s love. The reflective quality of melancholy renders trauma more bearable (Brady and Haapala 2003), reminding viewers of hope and love for their future, rather than becoming trapped in the negativity of their trauma. As viewers stand inside the box, resonating with their personal experiences and engaging in introspection, melancholy is evoked, ultimately releasing them from the grip of their trauma and allowing for an aesthetic moment of reflection and emotional connection. It is through this convergence of melancholy and aesthetic appreciation that viewers find solace and meaning within the artwork, creating a transformative and resonant encounter.

In this space (aesthetic moment), the reader, text, and author are held by the poetic. After this experience, we are both released – the reader to continue to re-create the text in his own thematic image, the text to pursue its intended course. (Bollas 1978)

Bringing my traumatic experiences to the public realm has been a challenging endeavour, yet the affective responses to My Bed (2022) and Love & Pain, Pain & Love (2022) have highlighted the potential of immersive installations to embody and convey complex emotions. The strategic use of found objects in sensory experience, and a melancholic aura in contextualised spaces, not only facilitates a deep understanding of my trauma but also serves as transitional objects for viewers, allowing them to delve into their own inner worlds and express their emotions when the artwork resonates with their personal memories. Moreover, this immersive experience encourages continued contemplation and has the power to effect change in their lives. Although the journey of healing from trauma is arduous, the process of creating these artworks has provided me with an avenue to recognise and release my emotions in a positive manner. The act of reflection and the resonance experienced by viewers have reinforced the possibility of transforming my negativity into cathartic art and have empowered me as an artist to give voice to others who are also navigating their own traumas. In this way, my artwork becomes a catalyst for healing, connection, and advocacy.

Reference list

Bollas C (1978), The Aesthetic Moment and the Search for Transformation. Annu. Psychoanal, 6:385-394.

Bennett J (2005) ‘The Force of Trauma’, in Empathic Vision: Affect, Trauma, and Contemporary Art, Stanford University Press, doi:10.1515/9781503625006.

Brady E and Arto H (2003), ‘Melancholy as an Aesthetic Emotion’, Contemporary Aesthetics, vol. 1, no. 6.

Cooke R (15 Oct 2007) ‘My Art is a Form of Restoration’, The Guardian, accessed on 26 May 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2007/oct/14/art4

Gronau B (2019) ‘Unexpected encounter On Installation Art as Immersive Space’ in Staging Spectators in Immersive Performances : Commit Yourself!, Taylor & Francis Group, New York.

Kaprow A (1966), Assemblage, Environments & Happenings, HN Abrams, New York.

Kaprow A (1958), Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life, University of California Press, London.

Patricia T (2019), Creative States of Mind: Psychoanalysis and the Artist’s Process, Taylor & Francis Group, New York.

TATE (3 April 2015) ‘Tracey Emin on My Bed’, TATE, YouTube video website, accessed 24 May 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uv04ewpiqSc&ab_channel=Tate

Werner A (2020), Let Them Haunt Us : How Contemporary Aesthetics Challenge Trauma as the Unrepresentable, Columbia University Press, doi:10.14361/9783839450468

Winnicott D (1953), ‘Transitional objects and transitional phenomena: a study of the first not-me possession’, The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, Harvard University Press.